A few weeks ago, the Bangladesh Energy Regulatory Commission (BERC) announced that a 12-kilogram LPG cylinder would cost Tk 1,306. On paper, that is the maximum retail price. Try telling that to a family in Dhaka or Chattogram who have just paid Tk 2,200 or Tk 2,400 for the same cylinder or been told that there is "no stock" at any price. This gap between the official story and the street reality is no longer a minor irritation. For millions of households that depend on LPG to cook their daily meals, it is a direct hit to food security and to already strained budgets. It also signals that something is badly wrong with how we regulate, price, and police this essential fuel. The good news is that the LPG mess is not inevitable. If we are willing to adjust both the pricing formula and the incentives along the supply chain, Bangladesh can move from today’s fire-fighting to a fairer and more predictable LPG market that works for consumers, retailers, importers, and the state.

The formula says one thing, the market does the other

Since April 2021, BERC has been fixing LPG prices every month using a formula tied to the Saudi Aramco Contract Price (CP). The regulator adopts the international benchmark, adds freight, port, and handling charges, taxes, and standard margins for importers, distributors, and retailers, and publishes a per-kilo ceiling that translates into a set of maximum retail prices for different cylinder sizes. For January 2026, this calculation produced an official price of Tk 1,306 for a 12 kg cylinder, up from Tk 1,253 in December. In November, the same cylinder cost around Tk 1,215. Month to month, the pattern looks measured and technocratic: small adjustments in line with movements in global LPG prices and the exchange rate. But anyone who actually tried to buy a cylinder in late December or early January knows a different story. Across many urban neighbourhoods, consumers have reported paying Tk 2,000 to Tk 2,500 for a 12 kg cylinder, often after visiting multiple shops.

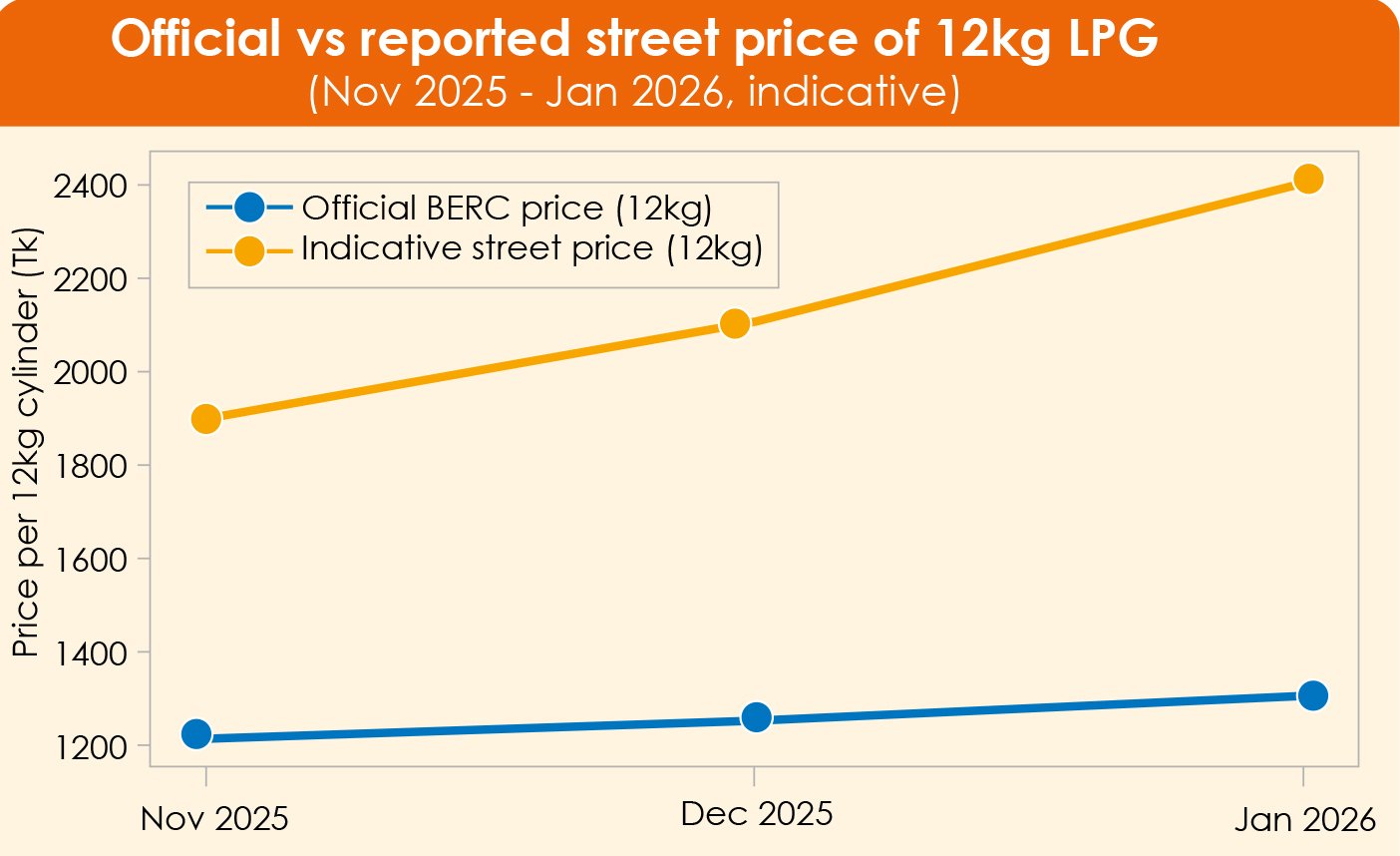

Figure 1:Official BERC price for a 12 kg LPG cylinder versus indicative average street prices in selected months. The chart illustrates how the formal price adjustment has been much slower than the jump in what consumers report paying.

In some areas, retailers have said there is no supply. Importers and some officials point to familiar pressures: difficulties in opening letters of credit, higher freight and insurance costs, shipping delays, and the lingering effects of sanctions and disruptions on global energy trading. By the time a cargo reaches Mongla or Chattogram, the effective cost per tonne can be higher than what the formula assumes. Consumer groups and many media outlets emphasise another part of the story. The Consumers Association of Bangladesh (CAB), for example, has warned of "artificial shortages" and "syndicates" in the LPG and essential goods market, suggesting that some actors in the supply chain are restricting supply or pushing up prices beyond any reasonable cost increase.

The truth is that both sides capture part of the reality. There are genuine cost pressures in bringing LPG into a country with tight foreign exchange and higher financing costs. There are also clear signs of distortion and abuse in a market where enforcement is weak and information is limited. If we focus only on one side, we miss the opportunity to fix the system as a whole.

LPG is now a basic fuel, not a middle-class luxury

LPG used to be seen as a modern cooking fuel for middle-class households. Today, in large parts of urban and peri-urban Bangladesh, it is effectively a basic fuel. Where piped gas is not available, and electricity is expensive or unreliable, households lean heavily on LPG cylinders. In economic terms, household demand for LPG for cooking is "price inelastic" in the short run. When the price doubles within a few weeks, families cannot simply stop cooking. They cut back on other expenses, borrow from relatives, or reduce the quality and quantity of food they prepare. If high prices persist, some switch back to dirtier fuels such as low-grade biomass or kerosene, with obvious health and environmental consequences.

On the supply side, importers must pay for LPG in dollars. They face foreign exchange rationing, higher bank charges, and sometimes demurrage charges if ships wait too long at congested ports. Distributors and retailers, in turn, handle heavy cylinders that must be transported, stored, and delivered safely. They face leakage, damage, and the risk that customers cannot pay on time. If the regulated margins at each level do not reflect these realities, actors in the chain will look for ways to compensate. Some will quietly add informal mark-ups. Others will cut corners in service or simply withdraw from the market until conditions improve. The result is what we are seeing now: a formal pricing regime that looks neat on paper, and a parallel reality in which the poorest households pay some of the highest effective prices per kilogram of cooking fuel.

A key clarification: this is about reforming BERC’s framework, not ignoring it

Before going further, one point must be clear. Nothing in this proposal suggests that retailers should ignore BERC’s existing LPG price orders, or that market forces should override the law. The recommendations here are aimed at BERC and the government themselves: they describe how the current regulatory framework could be reformed so that the official formula better reflects real costs, and the official price is actually enforceable in practice. In other words, this is a call for formal, transparent change in the rules, not for anyone to break the rules that exist today.

Short-run: a crisis band instead of a fictitious single price

In the next three to six months, the priority is straightforward: cylinders must be available at prices that may be painful but are at least tolerable and predictable. The worst abuse needs to be shut down quickly. One practical step would be to move from a rigid single number to a narrow crisis band. Instead of only announcing Tk 1,306 for 12 kg, BERC could declare, for example, a reference price of Tk 1,306 and a permitted retail band of, say, Tk 1,280 to Tk 1,380 for that cylinder size during the crisis period. Within this band, retailers would be considered compliant. This respects the reality that costs vary somewhat between locations. At the same time, any price above the top of the band would trigger presumptive violations, fines, and, for repeated cases, licence suspension. A Tk 2,300 cylinder could no longer be explained away as a small variation; it would clearly fall into the abusive zone.

Legally, this can be done within BERC’s existing powers. The commission already sets a maximum retail price. It could set the band ceiling as the MRP and publish the reference price inside that. Selling above the ceiling would remain illegal, just as today. Retailers could still discount below it if competition or local conditions allow. To make a crisis band meaningful, supply must also be unlocked. The government can support this with a time-bound LC and a working capital window for licensed LPG importers. Rather than crowding out the private sector, any imports by the Bangladesh Petroleum Corporation could complement private cargoes. In exchange for access to a special LC or FX line, participating importers would commit to publishing their monthly import volumes and respecting the BERC price band, with random audits of their stocks.

On the enforcement side, Bangladesh needs to move away from a model based mainly on sporadic raids. It would be easy to build a simple mobile tool – via SMS, USSD, or QR code – that lets consumers check the current official band for their cylinder size and district and report any outlet charging well above it. If the Directorate of National Consumer Rights Protection and BERC published weekly reports summarising actions taken, the message would spread quickly: systematic overcharging is now risky, not routine.

Finally, the poorest households need targeted protection. Instead of trying to subsidise all LPG for everyone, the government could use existing social safety net databases to provide a small, time-bound LPG transfer to vulnerable families. This might cover part of the cost of one small cylinder per month, or take the form of a modest cash transfer via mobile money. The objective is not to insulate everyone from any price increase, but to prevent the most vulnerable from being pushed into hunger or debt by fuel price shocks.

Medium-term: make the formula credible and the market contestable

Crisis tools can buy time, but they do not remove the underlying vulnerability. If Bangladesh simply waits for global LPG prices and the foreign exchange situation to improve, the next shock will produce the same scramble. The medium-term task is to make BERC’s pricing formula transparent, credible, and compatible with real competition. The first step is full transparency. Every month, alongside the new price, BERC should publish a simple breakdown of the official per-cylinder price: the international benchmark component, freight and insurance, port and handling, taxes and duties, and the margins at importer, distributor, and retailer levels. Right now, parts of this are known but not presented in a simple, consistent way. A clear breakdown would shift public debate from “the price is arbitrary” to “this component is too high” or “that tax is too heavy”. It would also make it easier for policymakers to see where reform is possible and where there is little room to move.

Figure 2:Illustrative build-up of the official 12 kg LPG price (Tk 1,306), showing each component in taka and approximate US dollars (assuming 1 USD ≈ 120 Tk). This kind of transparent breakdown would help clarify which part of the chain drives price changes and where reforms should focus.

.jpg)

Second, BERC should strengthen the way it reflects foreign exchange and financing shocks in its formula. If the taka depreciates sharply, or if financing costs and demurrage charges rise significantly, those realities should be captured transparently in the formula, rather than being treated as a separate excuse for market behaviour. This does not mean fully passing through every shock to consumers, but it does mean being honest about where pressures are coming from.

Third, in the medium term, LPG pricing should move towards a formula plus cap model. The formula would continue to define a justified wholesale cost at the depot gate, based on CP, freight, FX, and local charges. BERC would then set a maximum retail price for each cylinder size. Within that ceiling, companies and dealers could compete on price, delivery, and service quality. This is different from today’s one-number-everywhere logic. It accepts that some competition at the retail level is healthy and can benefit consumers, provided there is a clear upper limit enforced by the state.

Figure 3:Both models use the Saudia CP-based formula; the proposed approach makes it transparent and pairs it with a clear legal cap, so enforcement targets only serious overpricing while allowing some flexibility below the ceiling

.jpg)

Fourth, the margins allowed for distributors and retailers need to be updated on a professional cost-of-service basis. BERC can commission a study to map the real costs faced by typical dealers: transport routes, rents, wages, leakage, bad debts, and so on. If the current legal margin per cylinder is genuinely too low, it should be adjusted upwards to a realistic level. In return, dealers’ associations should commit to a clear code of conduct and accept meaningful penalties, including the suspension of licenses for persistent overpricing.

Finally, the structure of the LPG market needs attention. A sector dominated by a small number of importers with limited storage will always be vulnerable to supply holidays and poor coordination. Licensing should encourage more qualified entrants with their own storage and distribution capacity, subject to strict safety and technical standards. Over time, Bangladesh can also explore modest LPG storage obligations or joint storage facilities that increase resilience to global disruptions.

Who stands to gain?

The objective of these reforms is not to take the side of one group against another. It is to redesign incentives so that doing the right thing is more profitable and less risky than exploiting loopholes.

Consumers stand to gain from a price system they can actually see and understand. If BERC publishes a clear breakdown and a realistic band or cap, and if people have a simple way to check and report prices, the scope for blatant exploitation shrinks. Targeted support for the poorest helps ensure that basic cooking needs can be met even in periods of high international prices.

Retailers and distributors would gain from a margin structure that is grounded in their real costs, not in assumptions from another time. If the legal margin allows them to operate sustainably, many will prefer to stay on the right side of the law rather than risk fines and licence loss.

Importers would benefit from a formula that more accurately reflects the cost of sourcing, shipping, and financing LPG into Bangladesh. Time-bound support on LCs or foreign exchange during crises would reduce the temptation to delay cargoes or quietly squeeze supplies when conditions are difficult.

For the government and BERC, the gain is political as much as technical. Instead of being trapped in a cycle of low credibility and constant accusations, regulators could explain, defend, and adjust a system that is visibly more transparent and fairer than the status quo. Interventions in the LPG market would look less like panic and more like policy.

A small test of a bigger shift

The LPG cylinder crisis is only one part of Bangladesh’s wider energy story. It sits alongside rolling electricity load-shedding, foreign exchange pressures from fuel imports, and the broader challenge of moving towards cleaner and more secure sources of energy. Fixing LPG will not, by itself, solve all these issues. But it is a concrete and manageable test of whether the country can design reforms that combine economic logic, regulatory clarity, and basic fairness. The upcoming national election in February 2026 gives the next government a natural moment to reset expectations. Whatever party forms the government, it will inherit both the problem and the opportunity. A practical LPG policy – anchored in BERC, but responsive to real-world costs and incentives, would be an early signal that the new administration is serious about protecting consumers, supporting legitimate business, and building a more resilient energy system.

Bangladesh does not need a miracle to solve its LPG crisis. It needs clear rules, honest numbers, and a willingness to treat cooking fuel not as a political football, but as a basic service that must work, quietly and reliably, in kitchens across the country every single day.

Dr. Shahi Md. Tanvir Alam, Visiting Researcher, RIS MSR 2021+ Project, School of Business Administration in Karviná, Silesian University in Opava, Czechia, Email: tanvir@opf.slu.cz /shahi.tanvir@gmail.com

Download Special Article As PDF/userfiles/EP_23_16_SA.pdf