The 'Conference of the Parties' or 'COP' is an annual event in which the governments of developed nations pledge to fund climate initiatives while developing countries agree to adhere to these commitments under the auspices of the United Nations (UN). Governments, or "parties," participate in the annual COP event as they are signatories to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, the international environmental treaties, the Kyoto Protocol (1997), or the Paris Agreement (2015). Global leaders, ministers, and negotiators assemble at the COP to deliberate and endorse strategies for tackling climate change and its consequences collaboratively. Civil society, corporations, international entities, and the media typically "observe" proceedings to enhance openness, and accountability, and provide a broader viewpoint at each COP gathering. Baku, the capital of the Republic of Azerbaijan located on the Caspian Sea, will host COP29 from 11 to 22 November 2024.

COP28, the inaugural summit of three successive COP meetings, took place in Dubai, United Arab Emirates (UAE), with the objective of 'resetting' global climate action—termed by the UN as the 'Roadmap to Mission 1.5°C'—to avert a rise in global temperatures exceeding 1.5°C above preindustrial levels. Dubai hosted the first COP28, while Azerbaijan and Brazil will host the second COP 29 in 2024 and the third COP 30 in 2025, respectively, to ensure consistency and progress throughout the three COPs. In 2023, the inaugural "global stocktake" of international efforts to combat climate change revealed that the world was significantly deviating from the targets established by the Paris Agreement. The UAE Consensus Agreement, the principal outcome of COP 28, defined the appropriate responses for the parties involved. COP 29, the second of the three COPs, seeks to obtain the required resources to materialize the climate actions. COP30 will seek to achieve consensus on the execution of a new series of nationally decided climate plans, referred to as "nationally determined contributions" (NDCs).

Climate finance represents one of the most contentious subjects in the negotiations. The prior climate finance objective, which sought to allocate $100 billion yearly from developed to developing nations between 2020 and 2025, was both emblematic and unmet, constituting hardly a fraction of the real necessary amount. Moreover, it was contentious, as developed countries did not achieve the target until 2022, and even then, only through questionable or double-counting practices. COP29 aims to formulate a New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) that corresponds to the requirements and objectives of developing nations. The US estimates that trillions of dollars are necessary for this goal. Developed and developing nations are at odds over the financial responsibilities, amounts, nature of the assistance (loans or grants), and mechanisms for accessing the funds. Funding is a contentious issue, as it involves deciding whether to prioritize mitigating the impacts of climate change, adapting to its consequences, or compensating nations for the losses and damage caused by climatic effects. During the NCQG discussions, developed nations persistently request financial contributions from developing and emerging countries for the climate mitigation fund, which is not responsible for massive greenhouse gas emissions and climate change effects. The developing countries have neither the resources nor the means to mitigate and adapt to the effects of climate change, not a fault of their own. The Western industrialized developed nations have been responsible for most greenhouse gas emissions. Historically, poorer countries have contributed none or a negligible portion of emissions, primarily due to a lack of electricity, industries, automobiles, and home appliances the powering of which needs fossil fuels. Although everyone must take action to combat climate change, justice demands that those who cause the climate effect shoulder a greater portion of the responsibility for finding a solution. Figure 1 shows that the Western industrialized developed nations polluted the planet with CO2 over several centuries and continue to do so. The CO2 emission of emerging nations China and India has recently started to rise mainly due to the relocation of energy-intensive manufacturing from the Western industrialized countries to China, and India to avail the opportunity of cheap labor and other emerging and developing countries are facing the same consequences under the banner of globalization.

In 2009, developed and industrialized countries in the West pledged to mobilize $100 billion annually for developing countries to adapt to climate change and mitigate greenhouse gas emissions. This included financial resources conveyed through bilateral, regional, and international channels, as well as private capital, utilizing various methods, such as grants, loans, and insurance.

In 2022, western developed nations finally secured $115.9 billion in climate money, consisting of roughly 85% in loans and insurance and 15% in grants, encompassing annual bilateral and international aid, underpinned by dubious accounting techniques for developing countries. However, low-income countries received a negligible portion of the total, with only about one-fourth going to Africa. Loans were the primary funding category, accounting for over 85% of the total, and were primarily allocated to middle-income and higher-middle-income countries. The countries that were most affected and vulnerable received negligible assistance.

The designated funds must be dedicated to climate initiatives in developing countries. It would promote low-carbon, climate-resilient solutions in energy, transportation, and agriculture, enabling developing nations to improve their climate goals. Nonetheless, achieving these goals necessitates a significant financial commitment. The United Nations predicts that emerging and developing countries, excluding China, will need approximately $2.4 trillion yearly by 2030 to meet climate goals. Are Western industrialized developed countries ready to give this amount to the developing countries? It is very unlikely.

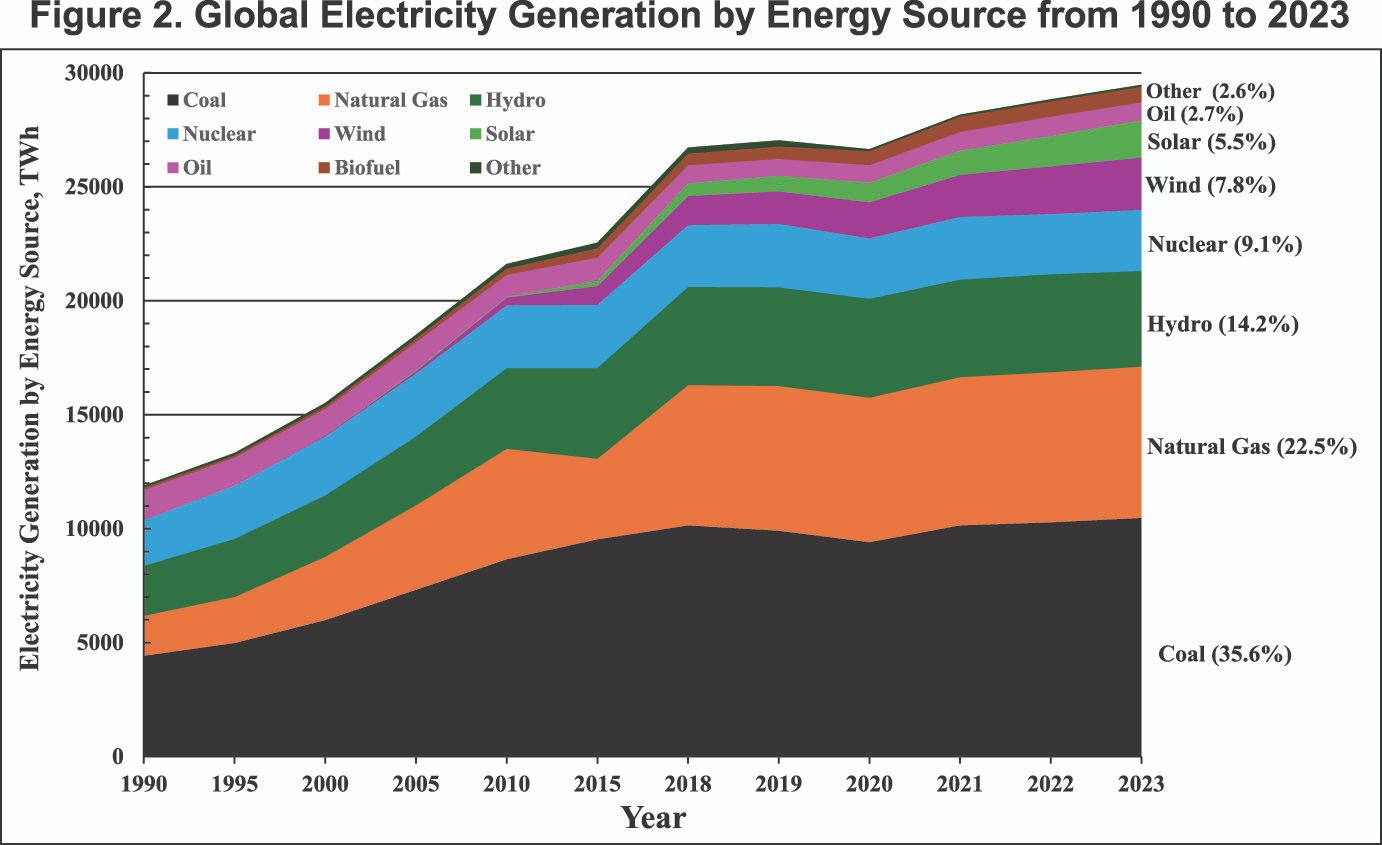

Currently, renewable energy sources are prohibitively expensive for developing nations. Western developed nations' existing policies aimed at transitioning from fossil fuels to renewable energy have largely failed or are on the verge of failing. The transition method demonstrates a notable divergence between projections and reality. Significant expenditures are necessary for the global transition from conventional energy sources, such as oil, coal, and gas, to renewable energy, which all countries currently rely upon (see Figure 2). Despite enormous effort and financial investment, the power generation by coal is hardly reduced as shown in Figure 2. The principal reason is the general affordability of renewable energy for two-thirds of the worldwide population, mostly in developing countries in Asia and Africa. As these countries prepare to embark on their national socio-economic development, developed countries must allocate essential resources to facilitate a sustainable energy transition. Due to the transfer of energy-intensive industries to emerging economies, industrialized Western nations are responsible for the recent increase in CO2 emissions in certain developing countries.

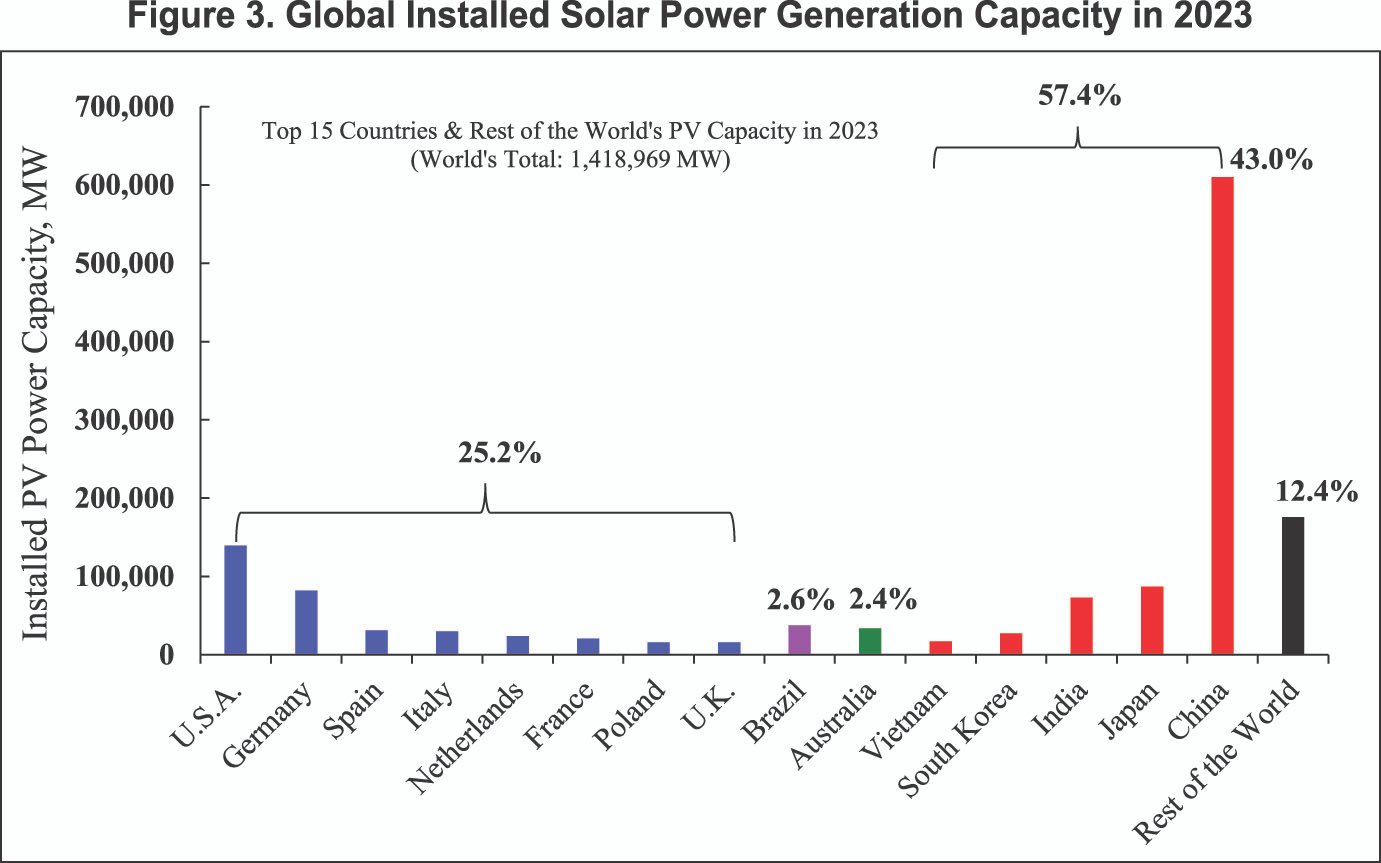

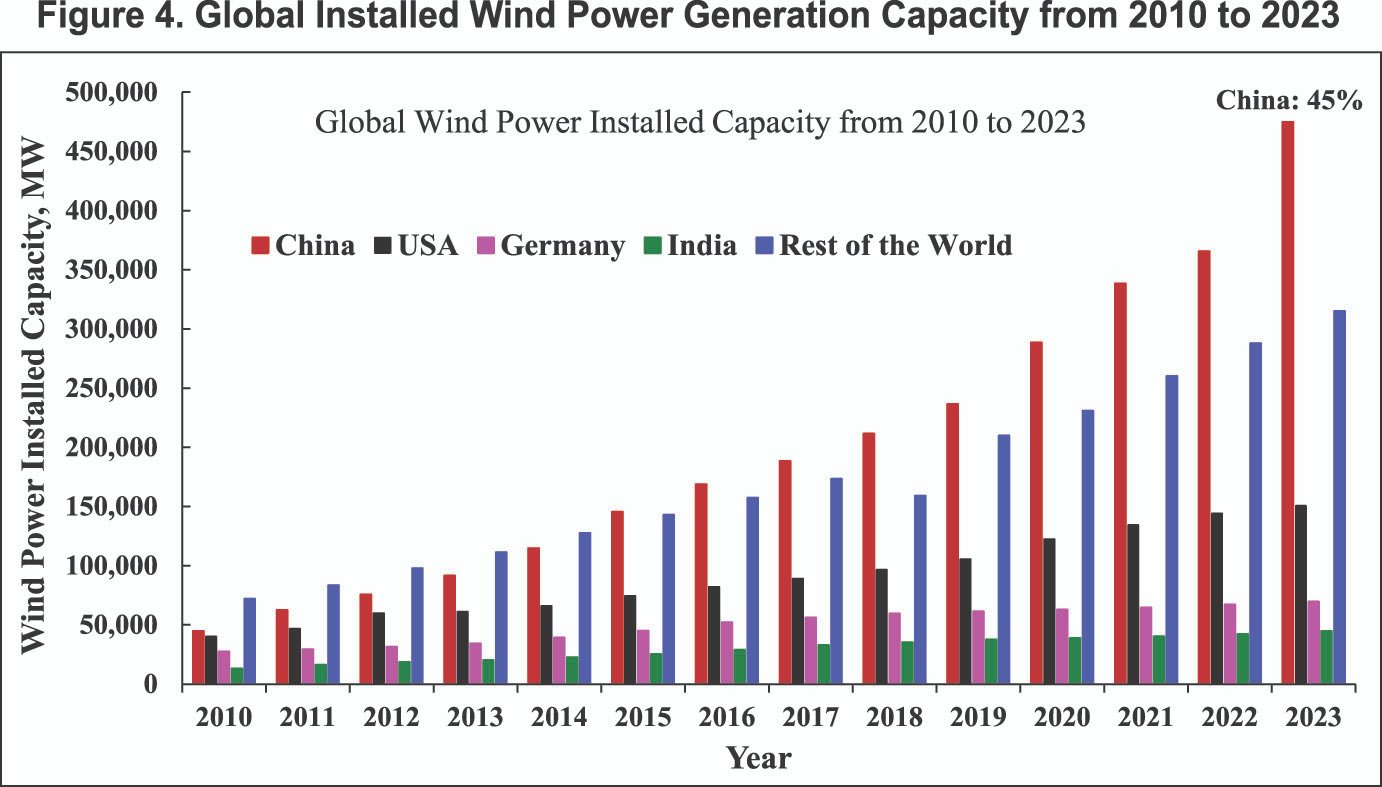

For example, Asia, the largest continent, comprises approximately 60% of the global population and gross domestic product while consuming nearly half of the world's energy supply. The existing transition planning fails to adequately integrate the perspectives and priorities of the continent. Fossil fuels account for 70% of electricity generation, whereas wind and solar energy contribute around 12%. Without China's contribution, the rest of the world's renewable energy accounts for less than 2% (see Figures 3 and 4). Oil consumption in Western developed economies, including the United States, has steadied at approximately 22 barrels per person annually. For the emerging and developing nations in Asia, the figures are 10 to 12 times lower, with Vietnam at 2.4, India at 1.4, and Bangladesh at 1.2 barrels per person. The per capita oil consumption is much lower in Africa. The most needed socio-economic development in developing countries requires over 100 million barrels per day for the foreseeable future, at least until 2050.

The global energy transition necessitates an investment of approximately US$100 trillion to US$200 trillion by 2050. Developing nations, prioritizing survival and exhibiting a per capita GDP 10–30 times lower than the Western developed countries, lack the resources to finance the energy transition. The prevailing ideals of the energy transition are impractical and must be anchored in considerations of affordability. The COP29 should prioritize the development of cost-effective technologies to reduce emissions from traditional energy, as well as the advancement of new energy sources and lower-carbon technologies that are competitive in price and performance.

Developing nations in Asia and Africa including Bangladesh, ought to determine an energy mix that corresponds with their national development priority and industrialization strategies, as well as their climate objectives, at a pace that is appropriate for them rather than adhering to the preferences of former colonial powers and western developed nations. Developing nations should refrain from signing any formal agreements that impose specific CO2 emissions reduction targets designed by developed countries, as such agreements may constitute a trap and impose significant financial burdens. COP 29 must prioritize the provision of secure, affordable, and sustainable energy for developing nations. Sustainability cannot be attained without guaranteeing security and affordability. Alongside new energy sources, conventional energy like oil and gas should continue to be included in the energy mix. In the Paris Agreement, developing nations were persuaded to commit to limiting global warming to 1.5 ºC to minimize the impacts of climate change. Developed nations are seeking to impose an expensive transition plan on emerging countries that is unviable, financially onerous, and impracticable, potentially endangering their economic progress and social unity. Therefore, developed countries must come forward with the promised financial support to aid developing nations in mitigating and adapting to the effects of climate change. If this fails to occur, the COP gathering will merely serve as a forum for discussions and empty promises.

Dr. Firoz Alam, Professor, RMIT University, Australia

Download Cover Article As PDF/userfiles/Cover Article(2).pdf