USD 79.6 Per Capita Climate Debt, Debt-to-Grant 2.7, Debt Trap Risk Score 65.37 out of 100 Warn

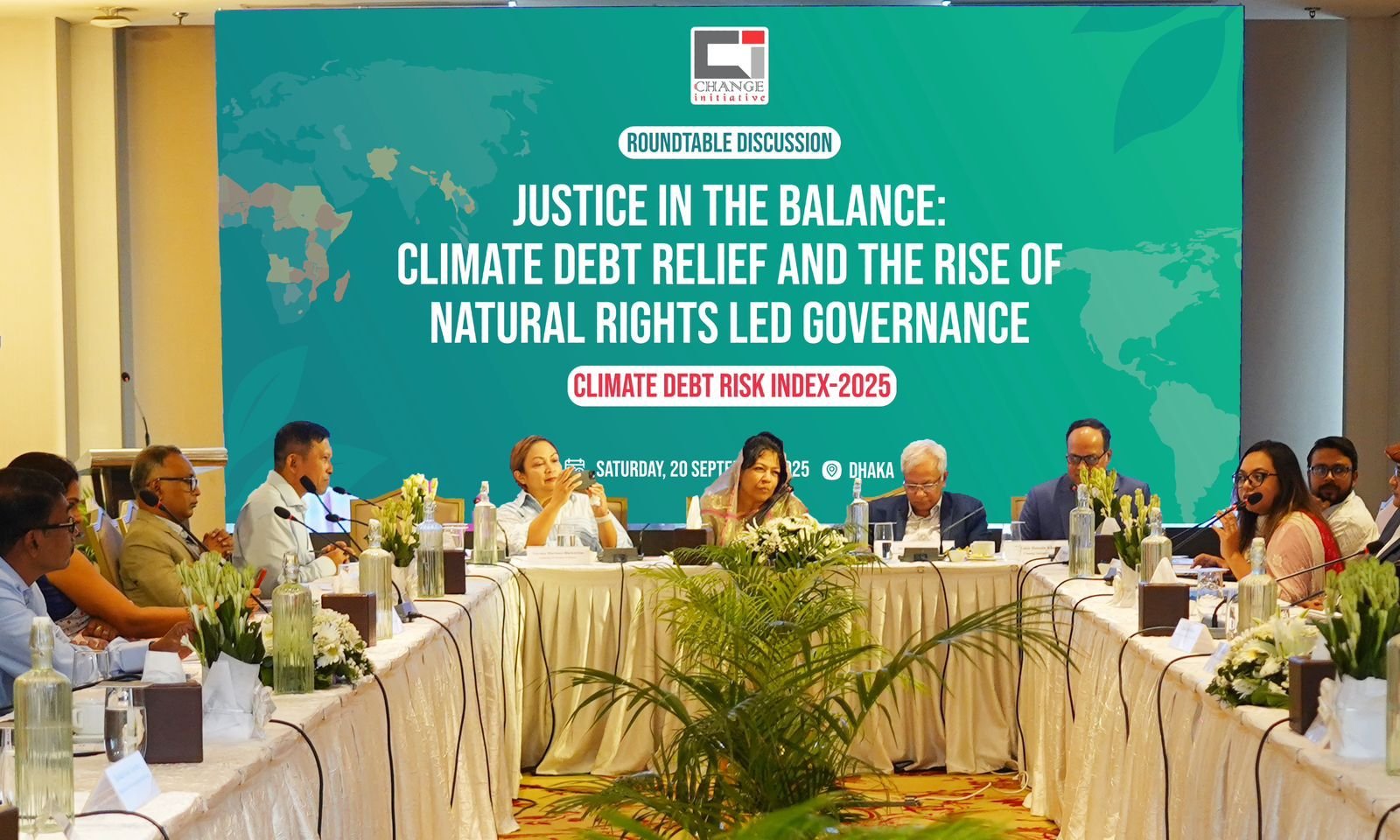

Dhaka, September 20, 2025 (PR) - Bangladesh has emerged as one of the most indebted climate-vulnerable country, according to the Climate Debt Risk Index (CDRI-2025) developed by Change Initiative. CDRI-2025 score for Bangladesh is 65.37 out 100, rising to 65.63 by 2031, putting Bangladesh in ‘High’ risk category. Despite contributing less than 0.5% of global emissions, Bangladesh now carries one of the highest per-capita climate debt of USD 79.6, with a Debt-to-Grant ratio of 2.7- almost quadruple of the LDC standard of 0.7 and the worst Multilateral loan ratio of 0.94, nearly five times of the LDC average of 0.19. The Index also finds Bangladesh’s Adaptation-to-Mitigation ratio at just 0.42, less than half the LDC average, leaving resilience efforts dangerously underfunded. The study was conducted by Change Initiative Research Team led by M. Zakir Hossain Khan and study findings presented by co-researchers Tonmay Saha.

.jpg)

The findings reveal how the international climate finance system- promised as reparations under the Paris Agreement- has turned into a “climate debt trap.” More than 70% of climate finance flows as loans, forcing vulnerable countries to pay twice: once through recurring climate disasters and again through spiraling debt repayments. Between 2000 and 2023, climate hazards displaced or affected over 130 million Bangladeshis and caused USD 13.6 billion in losses, yet adaptation support remains scarce while households privately shoulder BDT 10,700 (≈USD 88) each year on self-financed protection- adding up to USD 1.7 billion annually.

Bangladesh Highlights

• Per-Capita Climate Debt: USD 79.61 -one of the highest among LDCs, almost 4 times higher than the LDC average.

• Debt vs Grants: Debt-to-Grant ratio of 2.7, while the LDC average is 0.7.

• Multilateral Climate Loans: Multilateral Climate Funds’ debt to grant ratio of 0.94, nearly five times the LDC average (0.19).

• Adaptation Neglected: Adaptation-to-Mitigation ratio at 0.42, less than half the LDC average (0.88).

• For every ton of CO2e emission, Bangladesh is compelled to take a loan of USD 29.52, a clear injustice as per “Polluters Pay Principle”

• Sectoral Trap: Energy absorbs over half of climate finance but is overwhelmingly debt-driven (loan-to-grant 11.99:1). Transport and storage are near-total debt (1123:1), while water supply carries a ratio of 7.78:1 despite being adaptation-focused. Agriculture, disaster preparedness, health, and industry remain severely underfunded relative to risk and need.

Misattribution Scandal: 18.84% of Bangladesh’s reported “climate” finance has been misattributed to fossil fuel projects. These flows carry a loan-to-grant ratio of 28.8, inflating Bangladesh’s overall debt metrics and undermining genuine climate solutions.

Key Takeaways

• Bangladesh’s climate finance is debt-dominated, slow, and misaligned with life-saving adaptation.

• Households are privately financing resilience at scale while public finance arrives late and as loans.

• Misattribution of fossil projects as climate finance worsens debt metrics and undermines credibility.

• Without rapid correction, fiscal space will narrow, social spending will be crowded out, and hazard impacts will grow more lethal.

• A grant-first pivot and transparent classification standards are essential to avert a deepening debt trap.

The Pathway towards Just Climate Finance (Natural Rights Led Governance)

Bangladesh advances a practical pathway grounded in Natural Rights Led Governance (NRLG)- a governance approach that recognizes the inherent rights of people and ecosystems to exist, recover, and thrive, and treats climate finance as an obligation, not charity. Under this pathway, adaptation and loss-and-damage support must be debt-free by default, with direct, simplified access for local actors and transparent rules that prevent misattribution.

Immediate priorities under the pathway:

1. Grant-first finance – At least 70% of adaptation and 100% of loss & damage as grants; concessional debt only where economic returns are clear and equitable.

2. Debt exits and swaps – Cancel climate-induced debts; scale debt-for-nature/climate swaps tied to verifiable ecosystem restoration and resilience outcomes.

3. Direct local access – Empower municipalities, local institutions, and communities with simplified windows; invest in MRV and fiduciary capacity at sub-national levels.

4. MDB reform – Expand grant windows; rebalance toward adaptation; end fossil fuel misattribution; support country platforms for long-term systems change.

5. Earth Solidarity Fund – Establish a global grant mechanism capitalized by carbon pricing and transaction levies to deliver unconditional, country-owned resilience finance.

6. National reform – Transform the Bangladesh Climate Change Trust Fund into the Bangladesh Natural Rights Fund (BNRF) to anchor rights-based allocation and community stewardship, including new domestic sources such as pollution and carbon pricing.

Global Picture

Covering 55 countries, the CDRI 2025 shows 13 countries are on Very High-Risk, 34 countries are on High-Risk, 8 countries are on Moderate/Low Risk. Across all LDCs, over 70% of climate finance arrives as loans- a direct violation of the Paris Agreement’s polluter-pays principle and the International Court of Justice’s 2025 ruling on climate reparations. A full international release with country profiles and comparative metrics will follow at COP30.

Dr. Farhina Ahmed, Secretary, Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change: “Protecting biodiversity can reduce climate impacts, yet global forums like COP often fail to deliver results, leaving communities vulnerable. Bangladesh must respond by addressing unequal carbon emissions, as highlighted by the ICJ judgment, while prioritizing public-private action, national adaptation plans, and NDC implementation.”

Dr. A. K. Enamul Haque, Director General, Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies (BIDS): “Climate is science, yet Bangladesh remains deeply vulnerable. Grants are limited, loans risky, and overreliance on the private sector heightens financial strain. Vulnerable communities face added threats like trafficking. True resilience demands local knowledge, technology, and systemic change—incremental fixes are not enough.”

M. Zakir Hossain Khan, Chief Executive, Change Initiative: "Without firm pledges and clear governance, the $1B Climate Finance Action Fund, launched in COP29, risks remaining an ambition, not a lifeline for vulnerable nations”

Nayoka Martinez-Bäckström, First Secretary & Deputy Head of Development Cooperation, Embassy of Sweden in Dhaka: “Climate finance must be accountable, just, and impactful—protecting resources and ensuring a fair transition. Beyond grants, new financing sources are vital. Tools like the Climate Vulnerability Index and inclusive budgeting can guide allocation, but what matters most is real community impact. Only projects that truly advance adaptation and mitigation, such as public transport, should be prioritized to build resilience and support vulnerable populations.”

Dr. Fazle Rabbi Sadeque Ahmed, Deput Managing Director, Palli Karma-Sahayak Foundation (PKSF): Adaptation finance must be grant-based and equitable, or the world risks a climate debt crisis where survival becomes unaffordable for the vulnerable and destabilizing for all.”

Shirin Lira, Cooperation Officer, Embassy of Switzerlan: “Unless Bangladesh ensures accountability, transparency, and good governance so climate funds reach the most vulnerable, access to global finance will remain limited. Policies alone are not enough—during disasters, local communities are the first responders, and without building their capacity, international pledges will not deliver real action.”

Faria Hossain Ikra, Greenspeaker, Greenpeace South East Asia, “As Bangladesh prepares to graduate from LDC status, accessing just and fair climate finance will become even harder. We must explore how the ICJ’s advisory opinion can serve as a legal tool to hold major emitters accountable and mobilize the support we are owed.”

Dr. Saimun Parvez, Special Assistant to Chairperson, BNP “Bangladesh contributes little to global emissions yet suffers the greatest impacts. Climate finance must shift from loans to equity and justice, with transparency, accountability, and real support for adaptation. From nature-based solutions and waterway restoration to renewables and climate-smart agriculture, action must be backed by expertise, national commitment, and global solidarity. The era of climate debt must end; the era of climate justice must begin.”

Dr. Kazi Shahjahan, Joint Secretary, Economic Relations Division: “Climate science is intertwined with politics, economics, and human behavior; to effectively mobilize finance, we must navigate national and international policies, learn from global development frameworks, and build local capacity to utilize data and resources strategically.”