Overview: The Power Sector of Bangladesh

Bangladesh's economy is booming, and it was one of the countries with the fastest GDP growth in the world in 2019. Bangladesh is on its way to becoming a middle-income country, with the goal of being a developed country by 2041. Even the COVID-19 pandemic did not affect Bangladesh as much as it did in neighboring countries and similar economies. Bangladesh has weathered the worst fallout of the pandemic in 2020 and is well on its way to recover by 2022. According to the 2016 Power Sector Master Plan (PSMP)[1], total new installation capacity would reach 55,138 MW by 2041. This indicates that an average of more than 2000 MW of capacity will have to be added annually over the next 20 years to meet the expected demand until 2041.

Due to the tonal shifts in the global economy in a post COVID-19 world and the gradual decline of the fossil fuel industry, including a shift away from coal all around the world, Bangladesh also changed its stance by canceling major coal power projects in favor of Renewable Energy (RE)[2] and Cross-Border power trading. Bangladesh will diversify its power mix, lower the risks associated with variable fossil fuel prices, reduce the negative environmental impacts of fossil-fuel-powered generation, and remain competitive in global markets by switching to clean energy.

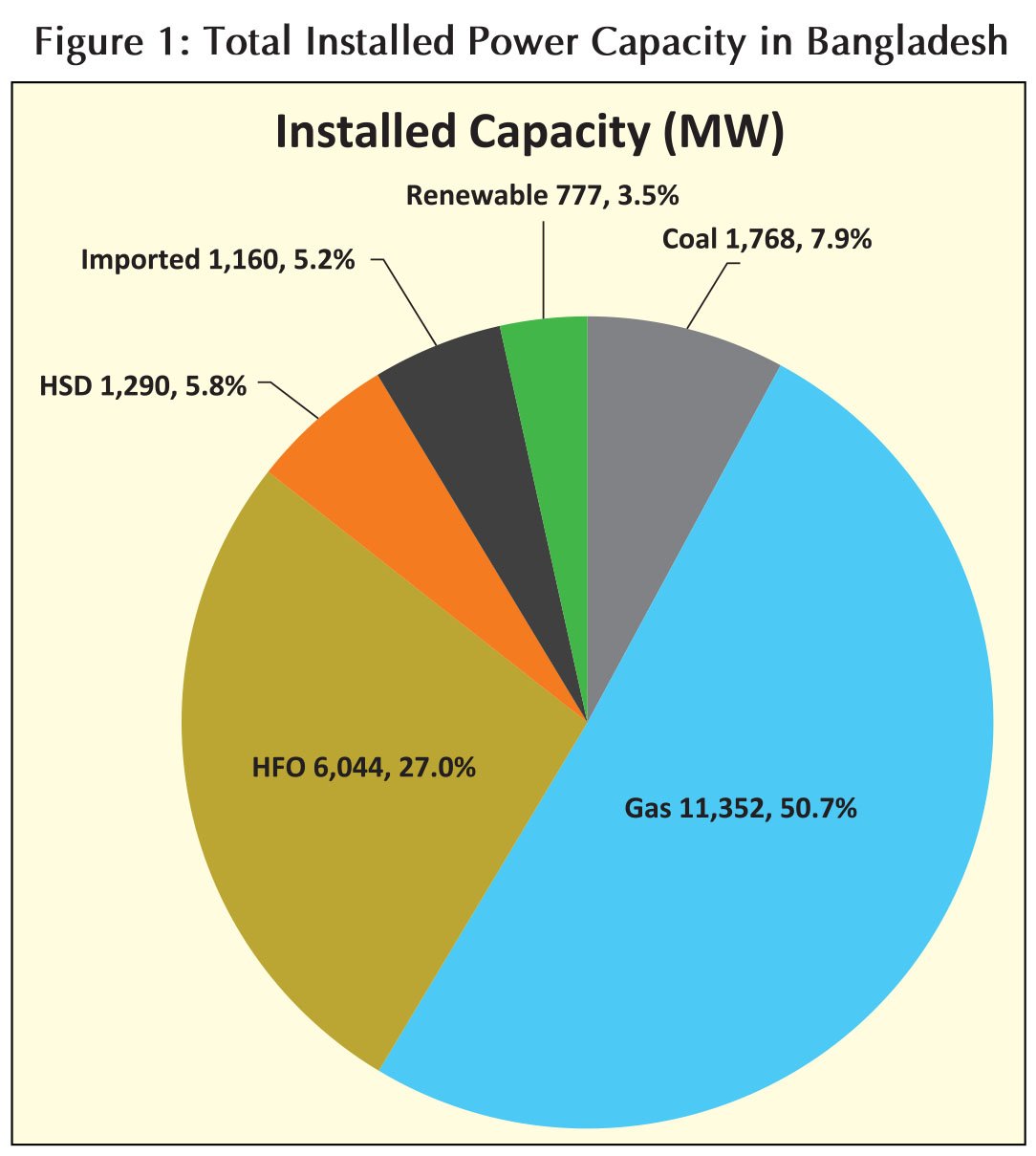

According to the Bangladesh Power Development Board (BPDB) and Power Cell, Bangladesh had 22,391 MW of mostly grid-connected and some off-grid RE installed capacity as of September 15, 2021,[3] with natural gas accounting for 50.7%, diesel and furnace oil accounting for 32.8%, coal accounting for 7.9% and renewable accounting for 3.5% of installed capacity.[4] It is worth pointing out that there is more than 3,000 MW of gas-based auto generation in industries known as “Captive Generation”. These are not connected to the grid and are operated by the industries because they consider grid power to be unreliable. The government has a long-term plan to stop captive power generation and bring these industries to the grid. SREDA had originally included captive power to total 11% of the total power capacity mix, which was not considered in this study.

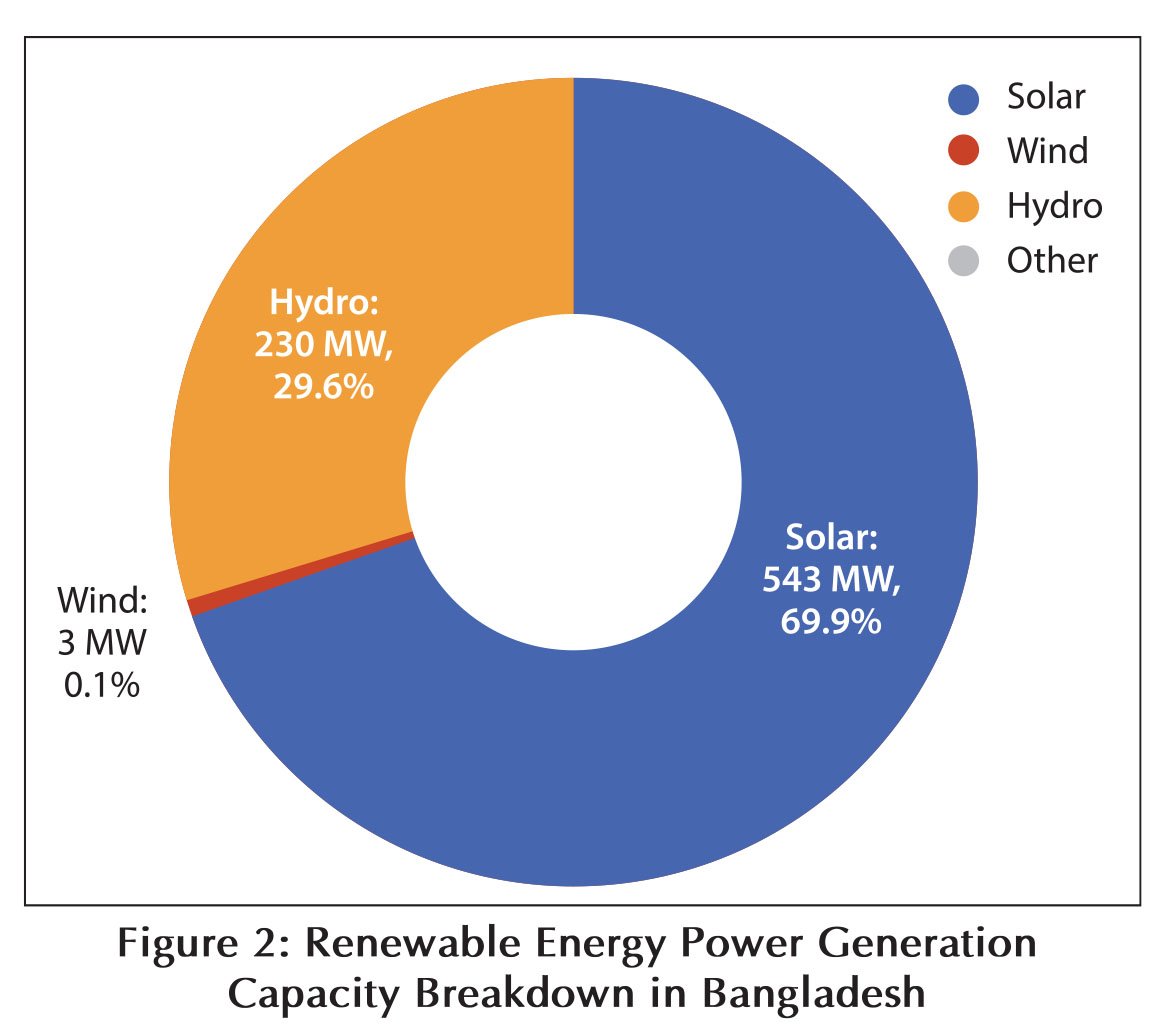

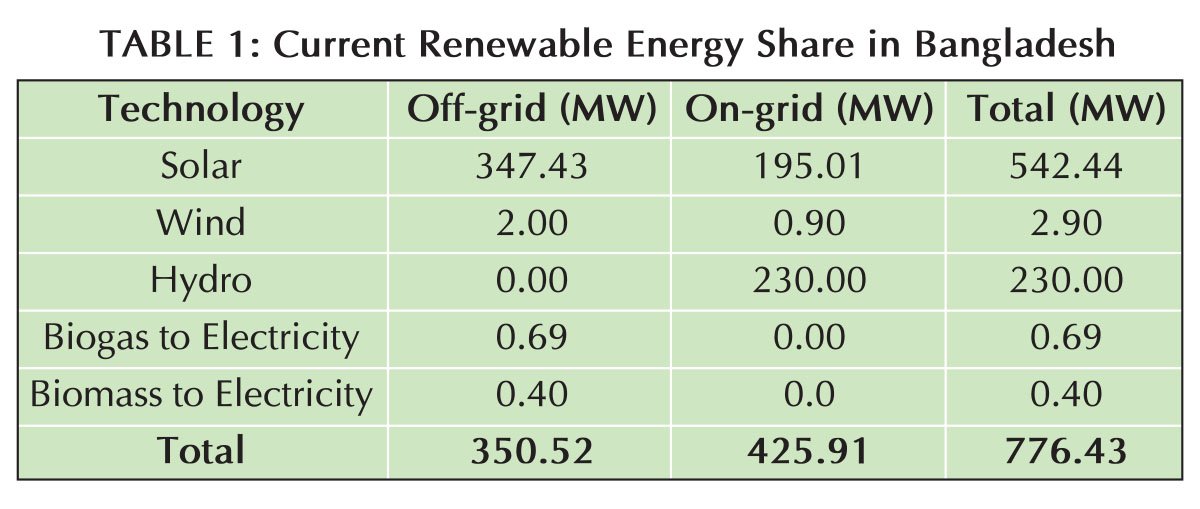

At 3.5%, RE consisted of the entire (both grid and off-grid) installed capacity of the Bangladesh power sector, but the fact that 1.1% is hydropower, which has remained static in generation since 1967, there has been very little actual progress. In addition, of the claimed 542 MW in solar power, grid-tied solar parks only contribute 195 MW (see Figure 2). Thus, of the target Bangladesh set itself for 2021 to install 10% of electricity capacity to be renewable, the country could only achieve 3.5%, majority of which is off-grid RE in that mix. Needless to say, Bangladesh has a huge challenge to increase its RE share. RE in Bangladesh is dominated by solar and the 230 MW hydro with other sources being very small in comparison, as shown in Figure 2.

[1]https://powerdivision.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/powerdivision.portal.gov.bd/page/4f81bf4d_1180_4c53_b27c_8fa0eb11e2c1/(E)_FR_PSMP2016_Summary_revised.pdf

[2] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-bangladesh-energy-climate-change-coal-idUSKCN2E410H

[3] http://www.powercell.gov.bd/site/view/powerdiv_achievement_at_glance/-

[4] http://www.renewableenergy.gov.bd/index.php?id=7

In the case of renewable energy, we see that the majority of the country’s renewable energy portfolio currently comes from off-grid solar, by virtue of around 6 million solar home systems installed in Bangladeshi households, mostly in rural areas, and the 230 MW Kaptai Hydropower Plant. The true picture of the current state of renewable energy adoption in Bangladesh cannot be ascertained because it is hard to document how many of the solar home systems are currently functional. This puts the 350 MW off-grid renewable energy claim into question. The Kaptai Hydropower Plant which has been around since 1967, is probably the last major hydroelectric source for Bangladesh with virtually no hydro potential of that magnitude available anywhere else.

Current Status of Renewable Energy Policies in Bangladesh

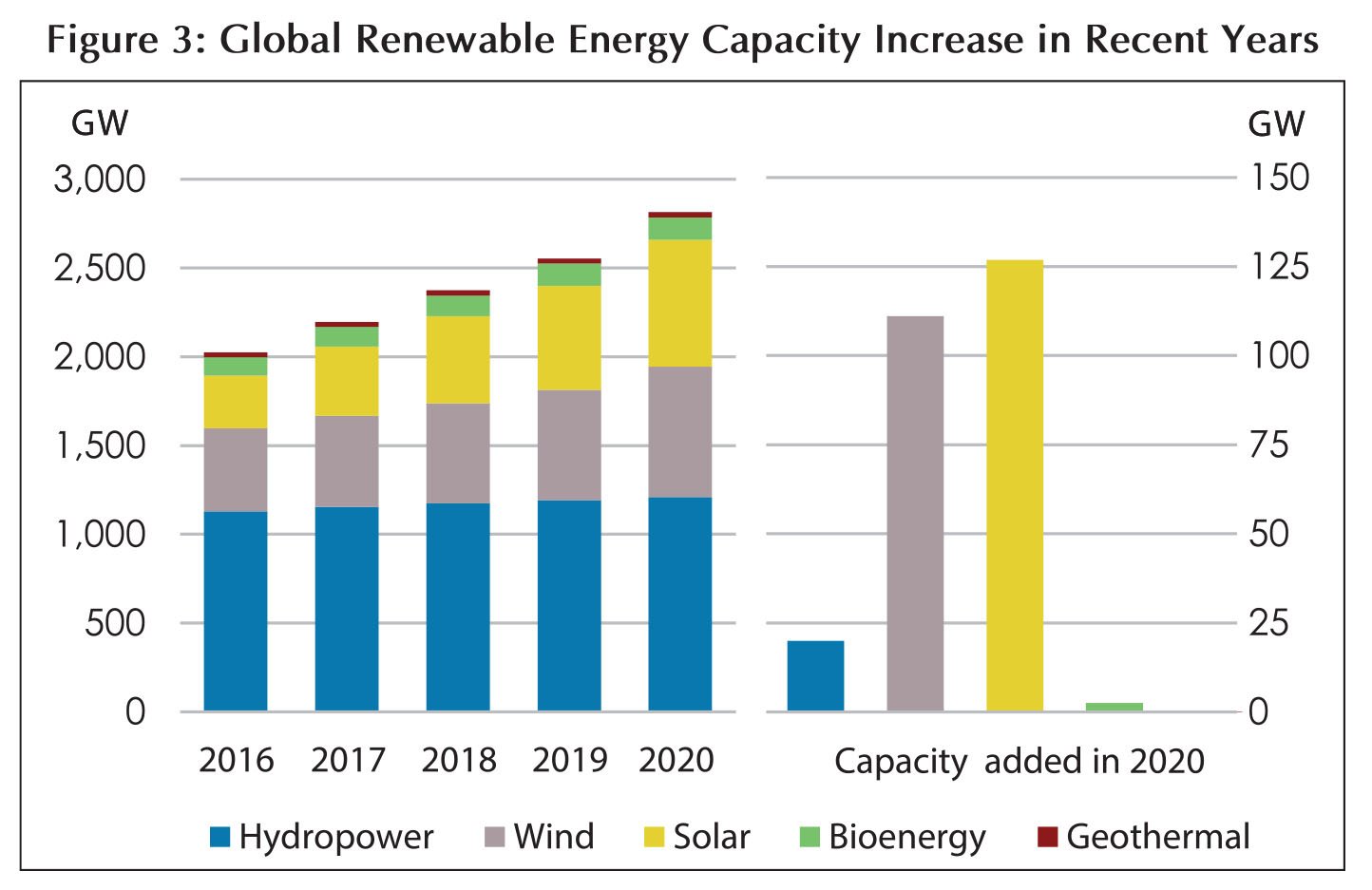

In recent years, RE has become a key source of new worldwide generation capacity. In the last decade, installed capacity has risen fast, from 1,223 GW in 2010 to 2,799 GW in 2020[1]. In-fact, RE consisted of about 60% of the new power additions in the world in 2020. It is safe to say that globally, research, development, and financial support will come to RE in the coming decades.

[1] https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2021/Apr/IRENA_-RE_Capacity_Highlights_2021.pdf?la=en&hash=1E133689564BC40C2392E85026F71A0D7A9C0B91

Bangladesh focused heavily on RE from the first Renewable Energy Policy in 2008. There are two contributing factors to that focus. The first is that Bangladesh is one of the countries that will suffer heavily if international efforts to combat climate change fail; the country is primarily low-lying and flat territory, with around 10% of the area being one meter above mean sea level.[1] Bangladesh has pledged under the Paris Agreement to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 7% below “business as usual” levels by 2030, and 17% below “business as usual” levels if international assistance is available. The second is that Bangladesh also took seriously the effort to diversify its fuel mix moving away from a power system heavy on gas. Although energy diversification at that time focused more on adding baseload power such as coal according to the Power Sector Master Plan PSMP-2010; subsequent revision in PSMP-2016 focused on LNG and cross-border power trading.

Private sector interest to invest in RE did not take off until 2011-2012 when the government included utility scale solar park bids under Unsolicited Proposal Policy as part of the Special Act and opened the door for a negotiated tariff. The 2009-2012 period can be considered as the inception phase in the policy landscape of RE development in Bangladesh. The major policies were conceived in the timeline, but the sector did not have any strategic focus. Therefore, private sector participation was scattered and many non-RE and non-power entities showed interest to build solar parks. Eventually, more than 50 Independent Power Producers (IPPs) received the letter of intent (LOI) in utility scale solar plants but they failed to bring most of them to commercial operation. Due to several institutional restrictions in the electricity sector, large-scale RE growth in Bangladesh has been very slow. These restrictions are mainly at the policy level, which makes it very difficult for serious players in the global renewable energy arena to invest in the RE Sector of Bangladesh.

Investing in RE in Bangladesh is challenging as is, due to several geographical, economic, institutional, technical and socio-cultural barriers. To ensure a sustainable energy future for the country, it is essential that the sector be accorded a high level of importance and priority by the government with favorable policies and incentives. Leading renewable energy countries like China, India, Germany, and the United States have already undergone a major shift from tax-credit driven investment to mainstream IPPs. For example, in India tax benefit in terms of accelerated depreciation for wind and solar power projects (~100-80% p.a. on the written down value) allowed private sector to enjoy large adjusted gross income and acquiring valuable assets in India.[2]

Similarly, governments in Middle Eastern countries, especially in UAE, allocated large amounts of land in their arid region for large scale RE projects, making electricity prices from solar come down to approximately 2 cents per kWh. However, the implications of such drastic cost regimes are not applicable in Bangladesh, where the RE IPPs are required to invest in the entire value chain of RE development, including building and maintaining the transmission line and access.

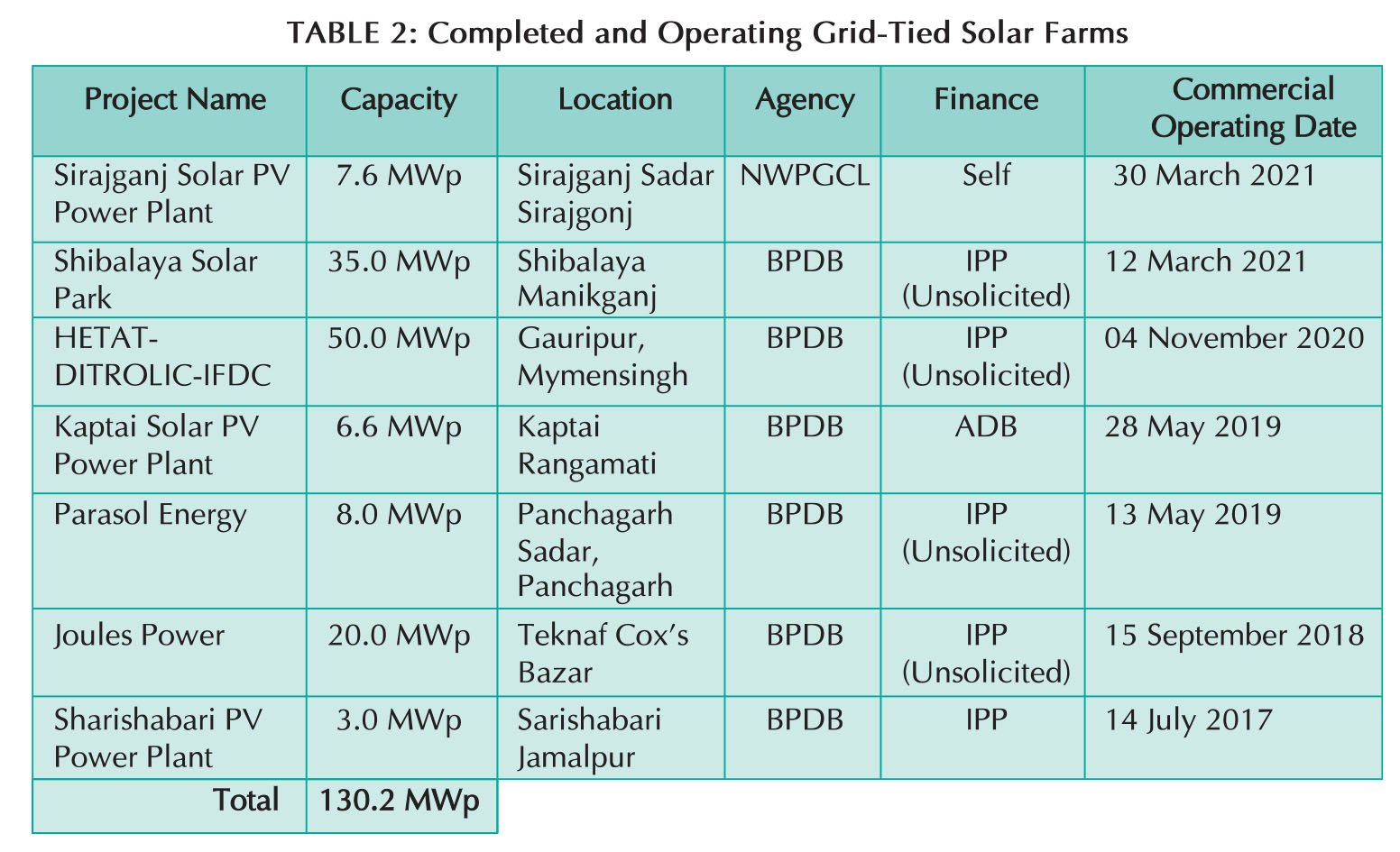

Despite the favorable investment environment, private sector enterprises who were the early adopters in the sector faced several challenges. As a result, the sector achieved slow growth and is still stuck in its nascent stage. The total accumulated investment by 2021 is estimated to be around $100 million[3], which is far below what is required to reach the target planned by the government. So far, most of the projects are IPP-driven, however, there is a trend that government power production companies such as BPDB, EGCB, CPGCBL, and NWPGCL are moving to develop their own solar projects. Table 2 enumerates the few successfully installed and operating projects.

[1] USAID, Bangladesh Climate Vulnerability Profile.

[2] BCG Report on Power Sector in Bangladesh, 2018

[3] Estimated with the thumb rule of 1 million USD per MW

Private Sector Challenges

The study has revealed numerous obstacles for RE companies in the Private Sector. These challenges pertain more to companies who have submitted a proposal, got an LOI and are waiting for approval. Besides that, acute challenges exist for projects which are currently under development or even running. Some of the major challenges are enumerated in Table 3.

TABLE 3: Major Challenges for Private Renewable Energy Companies

|

Stage |

Specific Challenge |

Major Implications |

Recommendation

|

|

Project Planning |

Site Selection, Energy Yield and Evacuation Planning |

-Ideally the solar plants are permitted to install in government owned or privately owned non-cultivable land. As an agricultural-based economy, Bangladesh has scarcity of non-agricultural land. Large amount of land is not available technically to implement large tier solar plant. High cost to settle land issue increase the risk burden for the investor.

-Whenever a land is selected, it is hard to get details around the transmission from one source. This leads to uncertainty over transmission loads in certain substations.

|

-Using low-lying lands, which are default non-agricultural and promoting productive dual use of these lands.

-Creating an open database where load forecasts are available for any developer. |

|

Partner Selection |

Local partners play a strong role to keep a regular contact with concerned government officials and local community leaders in the project’s location. Thereby, foreign partners have to rely heavily on local partners.

Conversely, Local Companies willing to do a solar project needs to have a foreign partner to show experience of at least 10 MW and for technical expertise and financing.

This dual requirement of partner selection means that it creates a lop-sided incentive system where foreign partners are tied up in a project in Bangladesh, and local partners feel compelled to hold the attention and interest of foreign partners for a long time. |

-Enabling local companies which have the triple expertise of

- Local knowledge and know-how

- Project planning capabilities and effective human resources

- EPC capabilities |

|

|

Financing |

Bangladesh has lower credit rating[1] than India or the Middle East which can be perceived as discouraging factor for foreign investors. Thereby, the cost of financing increases to cover the risk mortgage and insurance. This leaves development organizations with very stringent requirement and slow onboarding and Chinese financing.

In local market the interest rate is high (~6-9%), and due to lower credit rating cost of arranging finance is also comparatively higher in Bangladesh. In the Middle East cost of finance is around 1% of the total project cost whereas in Bangladesh it is around 2+%.

For financing a solar project, the market is heavily reliant on foreign partner companies. We have seen almost all the IPPs agree to an unrealistic deadline to close the finance deal since majority of their groundwork were delayed. In addition, securing low-cost financing from local sources is still very hard. The experience and creditworthiness of the sponsor is critical for achieving financial closure and obtaining attractive financing. Current renewable investment market in Bangladesh is still at its nascent phase. |

-Empowering organizations which can arrange their own funds to develop the renewable energy power sector |

|

|

Submitting the proposal |

The process of submitting an unsolicited proposal is not streamlined. Private sector stakeholders have shared a great concern regarding their risk and challenges due to lack of transparency in the process. |

-A one stop service where all the required information will be available. Also, increase the capacity of the mid-level officials in the government dealing with RE which will significantly reduce the time and effort.

|

|

|

Project Approval |

General Approval Process |

To build a solar project, IPPs need to collect almost 30 permits in a tight deadline. Lack of transparency and bureaucratic constraints compel foreign investors to take a step back and rely heavily on the local partners.

Some of the steps require vetting of land from the local offices, which creates even more challenges because it’s not a streamlined process. These kinds of regulatory reroutes create opportunities for corruption, mismanagement and unwanted delays. |

-One stop service would again be able to expedite project approvals. |

|

Power Evacuation |

Right of Way (ROW) |

Evacuation is an equally formidable challenge. Securing ROW for transmission lines is becoming more difficult for private sector since the right to make a way over the land involves clearance from all stakeholders including, landowners, forest department, roads and highway department etc., which make the process time-consuming leading to increases in cost to obtain the ROW and construct the transmission line. |

-Ensuring ROW is assisted or ROW is provided by the Government. |

|

Post Planning Evacuation Challenges |

After giving initial approval for the solar plant the authorities allowed other plants to evacuate power from the same existing infrastructure without any further expansion of the capacity. Therefore, existing substations were already functioning to their optimal or maximum capacity. In such cases, the solar plant was forced to restrict generation which eventually delayed the recovery of the developer’s investment. |

-Ramping up transmission planning and load planning in tandem with project development |

|

|

Future Challenges |

Lowering Cost of Peak Power and Grid Stability |

Renewable energy experts expressed concern about future solar plants’ integration into the grid as it is not robust enough to handle solar intermittent power beyond a certain capacity. Especially, if the solar PV systems are connected at 11 kV; then it is likely to be more challenging than connecting to 33 kV or 132 kV. |

-Government plans in smart grids capable of handling intermittent power is 10-15 years away.

-In the meantime, Government should adopt and promote Renewable Energy with Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) projects to curb high-cost peak power. Solar + BESS projects are increasingly becoming cheaper worldwide. |

SUMMARY of CHALLENGES: Policy Gaps

Summarized version of challenges in private sector renewable energy development from a policy lens is provided below –

1. Lack of Strategic Direction: The RE sector in Bangladesh lacks a clear strategic direction in terms of setting targets from specific technologies. Shifting government priorities have seen some technologies (Solar Home Systems, Mini-grid) being hamstrung. Different competing energy sources and power systems are also shifting the government’s focus from RE. Fuel Oil-based Quick Rental Power Plants from Small Independent Power Producers are still a major and costly portion of the power mix, and these need to be gradually phased out to make room for RE.

2. Failure of the early unsolicited utility-scale solar projects: Many large utility-scale power projects have failed to come on-stream in time, and the government had to extend the Commercial Operating Date, or allow change of partners, or allow change of locations, etc., to keep the projects alive. Failures of the early unsolicited solar projects have had a negative effect on the government to promote RE. A few bad actors from the early-stage utility-scale projects have deterred the government and private sector investors. Analyses of these failures revealed that the major points of contention were land availability and land acquisition, securing the ROW, and challenges surrounding grid-interconnection.

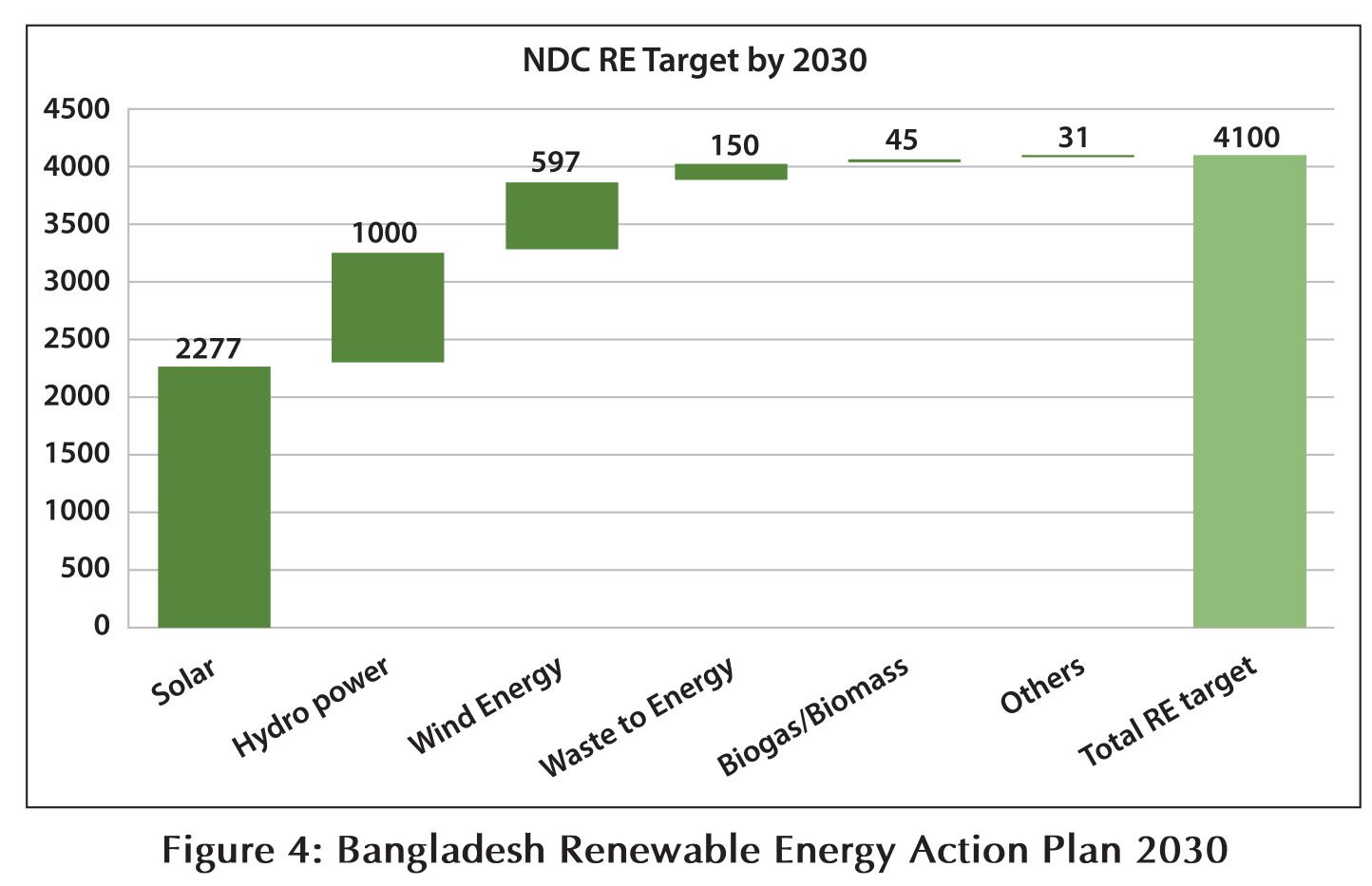

3. Lack of proper studies, Bankable Data, Regulatory Checklist in the Wind Energy Sector: The Private sector is exposed to a lot of risk in terms of acquiring reliable and authenticated data. There is a dearth of data in terms of land availability, substation load capacity, site specific data, etc. Although the wind energy sector has considerable potential in Bangladesh with a NDC target of almost 600 MW (see Figure 4), without proper policies and guidance in place, the sector remains at risk and untapped.

4. Investor/Lender interest surrounding uncertainties: In Bangladesh, to develop utility scale RE projects, Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs) are created with a partnership between a foreign company which typically brings technical expertise and global, low-cost finance and a local company which brings regulatory navigation and local logistics support. The way SPVs are designed, foreign investors/lenders are deterred over project timelines, interagency navigation, contract lock-ins (e.g., a local partner and their foreign partner need to be a part of the project for at least 6 years), lack of clarity over various regulations, etc. Research into the issue revealed that though a lot of local players received interests from reputed international developers/lenders, they ultimately shied away over delayed timelines and conflicting contracts. Local lenders were not equipped with proper lending mechanisms for utility-scale RE projects. The private sector feels the need for a guarantee mechanism to attract lenders.

5. Utility Distribution Companies Upgradation: The distribution utilities in its current state are inadequate to support mass RE adoption to serve the local electricity market. The underlying problems are two-fold; first, in the infrastructure readiness and planning level, and second, in terms of capacity and preparedness of many local level offices. For mass renewable adoption at the Upazila level, the key utility agency is the Rural Electrification Board (REB). The 33 kV lines maintained under REB are prone to frequent outages. The distribution utilities are also currently ill-equipped to adopt net-metered solar rooftop systems, making the incentives hard to avail.

IMPLICATIONS of COP26 OUTCOMES

This year’s event of COP26 was a landmark in the fight against climate change. Following the UN’s IPCC[2] report, the 200-country delegation unanimously named fossil fuels as the primary reason for climate change. As such, all the major development banks are now shying away from coal[3], and Bangladesh could soon be ostracized if coal remains a major part of its fuel mix. Bangladesh has announced bold plans around renewable energy adoption in COP26. The Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) talks about a target of 4,100 MW renewable energy by 2030. The initial plan has laid out a strategy of including renewable energy sources disaggregated by technology. The plan laid out is shown in Figure 4. However, these plans would be hard to mobilize from a private sector perspective if incentives are not provided to reduce consumption by the end-user and regulatory reforms are not implemented.

[1] https://www.businessinsider.com.au/credit-ratings-asia-pacific-moodys-2018-1

[2] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Report: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_Full_Report.pdf

[3] https://www.reuters.com/business/sustainable-business/nearly-all-development-banks-committed-cutting-coal-investment-data-shows-2021-11-02/

Annex 1: List of Acronyms (in the order of appearance)

|

ACRONYM |

FULL FORM |

|

BUET |

Bangladesh University of Engineering & Technology |

|

GDP |

Gross Domestic Product |

|

COVID-19 |

Corona Virus Disease 2019 |

|

PSMP |

Power System Master Plan |

|

MW |

Megawatt |

|

SREDA |

Sustainable and Renewable Energy Development Authority |

|

LNG |

Liquefied Natural Gas |

|

RE |

Renewable Energy |

|

BPDB |

Bangladesh Power Development Board |

|

HSD |

High Speed Diesel |

|

HFO |

Heavy Fuel Oil |

|

GW |

Giga Watts (1,000 megawatts) |

|

GHG |

Green House Gas |

|

IPP |

Independent Power Producer |

|

LOI |

Letter of Intent |

|

p.a. |

Per Annum |

|

kWh |

Kilowatt Hour |

|

EGCB |

Electricity Generation Company of Bangladesh |

|

CPGCBL |

Coal Power Generation Company of Bangladesh |

|

NWPGCL |

Northwest Power Generation Company Limited |

|

SPV |

Special Purpose Vehicle |

|

NDC |

Nationally Determined Contributions |

Acknowledgement: The authors wish to express their sincere thanks to Mr. Salman Rahman for his valuable research and study of the RE sector in Bangladesh, which is the basis of much of the content in the report