The world today is gripped by war, division, and a renewed struggle for dominance. The Middle East remains on edge, and the Russia–Ukraine conflict shows no sign of resolution. As a result, the focus of developed nations has increasingly shifted toward military buildup and defense expansion rather than global cooperation. Once the torchbearers of climate ambition, these countries are now channeling resources into security and geopolitical influence. The return of protectionist trade policies, such as former U.S. President Donald Trump’s tariff measures, has further rattled the global economy and deepened uncertainty. Adding to this drift, the United States has withdrawn from the Paris Agreement for the second time, leaving a troubling void in global climate leadership.

.jpeg)

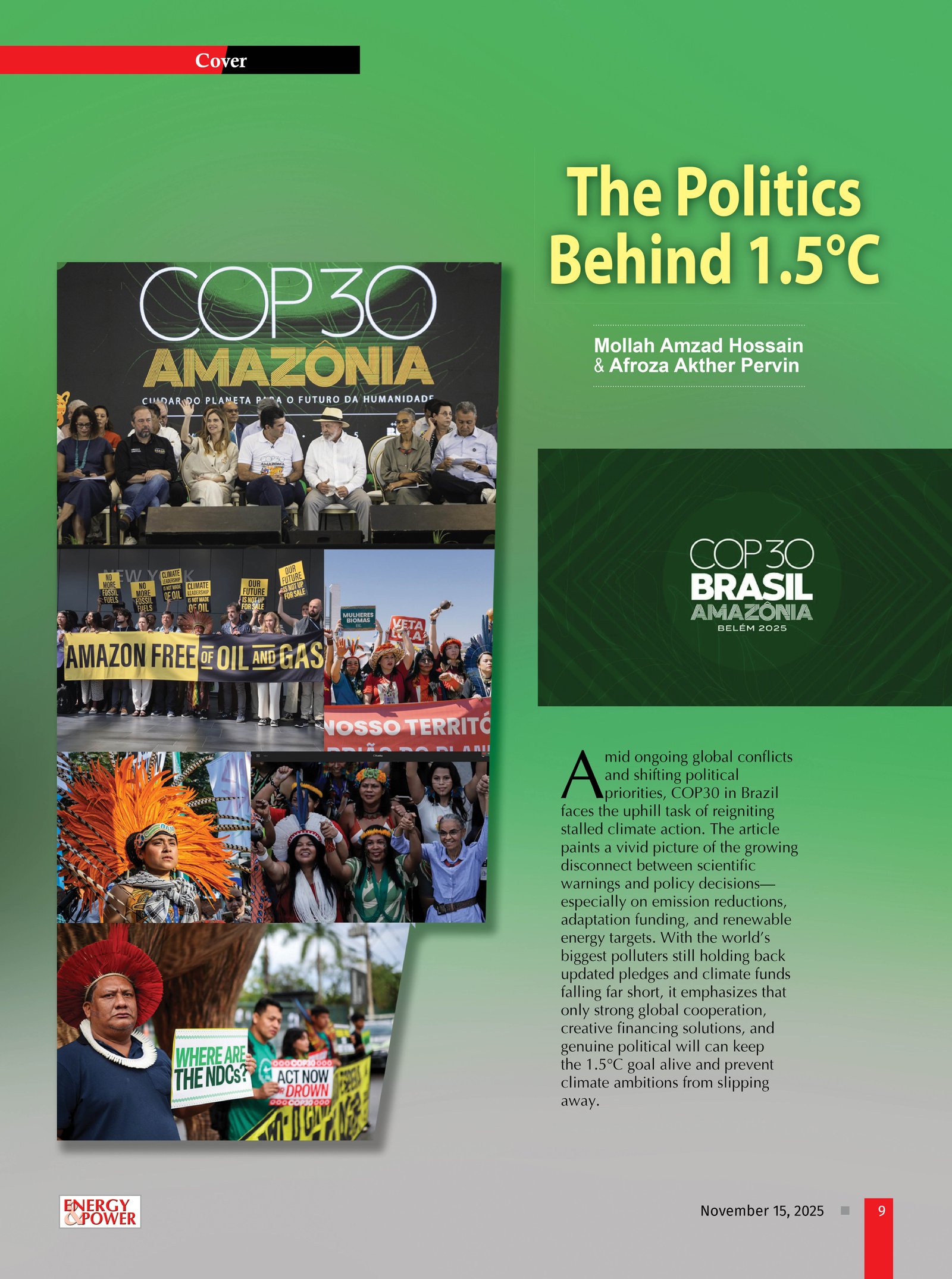

Against this turbulent backdrop, the world’s attention is now turning to the Brazilian city of Belém, located in the heart of the Amazon, where leaders and negotiators will gather under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) for the 30th Conference of the Parties (COP30). Beginning on November 10, the summit will aim to find common ground on how humanity can shield itself from the escalating threats of climate change and pollution. The venue itself – the Amazon rainforest, often called the “lungs of the planet” – is a poignant reminder of what is at stake.

Yet, even before discussions begin, disappointment hangs heavy in the air. Developing countries and civil society groups are dismayed by the lack of ambition shown in the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), the emission-reduction commitments central to the Paris Agreement. Despite multiple extensions, only 67 of the 193 signatories have submitted their updated NDCs (version 3.0), representing just 30% of global emissions. The world’s largest polluters – the United States, the European Union, China, and India – have yet to deliver theirs, leaving countries responsible for 70% of carbon pollution conspicuously silent. Under the Paris Agreement, every signatory is legally obliged to submit an NDC, but this fundamental obligation is being ignored at a time when action has never been more urgent.

The UNFCCC’s recent Synthesis Report paints a sobering picture. Even if all current pledges are fully implemented, global emissions will drop only 6% by 2030 and 17% by 2035 compared to 2019 levels. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), however, warns that emissions must decline by at least 60% by 2035 to achieve net zero by 2050. The gap between rhetoric and reality has never been wider – and the longer it persists, the harder it will be to limit global warming to 1.5°C, the critical threshold for avoiding catastrophic climate disruption.

.jpeg)

Climate negotiations have always been a delicate balancing act between science and politics. Within the UNFCCC framework, decisions are made not through voting but by consensus, making progress painfully slow and often hostage to national interests. This process, while inclusive in theory, has too often allowed politics to overshadow science and ambition. The result has been a cycle of promises unfulfilled and targets unmet, even as the planet’s temperature and climate risks rise relentlessly.

When asked about this, Professor Mizan R. Khan, Technical Lead of LUCCC, said: “It is now clear that keeping global temperature rise within 1.5°C is nearly impossible, as we are already approaching that level. But keeping the 1.5°C target alive as a pressure point is essential. If the world fails to reduce emissions significantly, the temperature could rise by 2°C by 2050 and reach 2.7°C or higher by the end of the century, leading to devastating consequences for humanity.”

Professor Dr. Ainun Nishat added: “There is no alternative to keeping the 1.5°C goal alive. Although temperatures may exceed projections by 2050, they could stabilize later. I believe the global leadership in Belém will take necessary steps to ensure that the 1.5°C target remains alive.”

According to Mirza Shawkat Ali, Director at the Department of Environment, China now accounts for 23% of global emissions, followed by the United States at 13%. “The positive side,” he said, “is that China is making massive investments in renewable energy expansion. Although the U.S. withdrew from the Paris Agreement, several states continue to implement emission-reduction programs. However, developed countries are showing little interest in providing the investments needed to limit temperature rise to 1.5°C this century. Therefore, it would be unrealistic to expect major breakthroughs in climate financing from the Belém negotiations. Still, discussions will likely continue on how to increase the climate fund from USD 300 billion per year starting in 2026 to USD 1.3 trillion by 2035. The reality, however, is that according to the Global South’s position, such financing cannot come entirely from the public sector—it will gradually decline. Hence, there is no alternative but to explore how to mobilize funds from the private sector and innovative sources, while continuing to pressure high-emitting nations to contribute.”

Amid this uncertainty and frustration, COP30 will commence in Belém on November 10 and continue until November 21, with one day’s break. Historically, Brazil has played a strong role in climate diplomacy. According to Ziaul Haque, Additional Director General of the Department of Environment: “Brazil is doing its utmost to keep the 1.5°C goal alive and secure financing. The country has sent 15 letters to nations around the world seeking support for these objectives, and ministerial-level dialogues have been held on the matter. However, the level of success remains uncertain, as current geopolitical realities are not in Brazil’s favor.”

Negotiators believe that the ‘Baku to Belém Roadmap for USD 1.3 Trillion’ will receive the highest priority at COP30. Based on the Baku decision, the annual climate fund floor must rise from USD 100 billion to USD 300 billion by 2026, and the roadmap to reach USD 1.3 trillion by 2035 will be discussed.

According to Dr. Manjurul Hannan Khan, Executive Director of the Nature Conservation Network (NACOM): “The world is far behind in setting a new scale for climate finance. It’s unlikely that the Belém negotiations will achieve significant progress toward the USD 1.3 trillion roadmap target.”

However, Ziaul Haque remains cautiously optimistic: “Brazil will continue its efforts to identify concrete sources of climate financing and announce a roadmap. It is true that full funding cannot come from the public sector—it will decline gradually. Therefore, we must clarify how the private sector can contribute to climate funds, alongside exploring ways to engage charities and wealthy individuals in climate financing.”

In essence, innovative financing means finding ways to raise funds through taxation on the wealthy and levies on airlines and shipping lines. The key challenge now is to define how such financing mechanisms can be established. It is expected that the Belém negotiations will focus more on identifying these financing channels rather than merely obtaining pledges of new funding.

Many climate experts believe there is little chance that historically high-emitting countries will, on their own, provide sufficient contributions to climate funds. Therefore, emerging economies must also be pressured to step up and contribute to financing efforts.

In an interview with Energy & Power, Md. Shamsuddoha, Chief Executive of the Center for Participatory Research and Development (CPRD), said: “It is becoming increasingly difficult to secure financing for climate action — particularly as grants. For example, in 2024, the total global development assistance amounted to USD 1.3 trillion, of which only 5.6% was in grants, while 80% came in the form of loans. Therefore, mobilizing investment to keep global temperature rise within 1.5°C has become one of the biggest challenges of the 21st century.”

To exert pressure on developed countries to fulfill their commitments, the Civil Society Federation has organized a three-day “Fotila” campaign during the Belém COP.

During a discussion on the issue, an Additional Secretary of the Economic Relations Division (ERD) AKM Sohel said that since independence, Bangladesh has received commitments of USD 187 billion in foreign assistance, of which USD 107 billion has been disbursed. Of this, 94.73% came as loans, while only a small portion was in grants across various sectors. Therefore, it is unrealistic to expect that all climate finance will come as public sector grants.

Instead, the Global South’s negotiators and civil society should push for arrangements allowing climate-vulnerable countries to access loans at 1% interest rates.

Alongside discussions on the new dimensions of climate finance, there will again be debate on finalizing the definition of “climate finance.” The Standing Committee on Finance will present its recommendations, but it is unlikely that developed and developing countries will reach an agreement. There is also a significant discrepancy between the OECD’s accounting of climate finance and that of international NGOs like Oxfam.

As a result, there will likely be discussions on establishing a dedicated institution under the UNFCCC to monitor and oversee global climate finance flows — though no concrete decision is expected yet. According to Professor Ainun Nishat, “It is unlikely that a decision will be made to establish such an institution now. However, these issues can be reviewed under the framework of the Global Stocktake (GST). The next GST will be held in 2028.”

While the Baku COP was dubbed the “Finance COP,” the Belém COP does not yet have a distinct label. However, one thing is nearly certain — from COP30, the world will adopt the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA). Still, it remains unclear how much financing can be secured to implement it.

Mirza Shawkat Ali believes that by reducing the number of indicators to around 100, the world will be able to finalize the GGA framework in Belém. However, the real test will be how successfully countries can secure financing, technology transfer, and capacity-building investments to implement it.

It is expected that the Belém discussions will emphasize ensuring that each country finalizes its National Adaptation Plan (NAP) in line with the GGA framework. As in every COP, negotiators will again push to allocate 50% of total climate finance to adaptation activities.

When asked about the matter, Dr. Mizan R. Khan said: “The world is currently preoccupied with wars and tariffs. Some developed countries are unwilling to provide financing, while others that want to invest in climate funds lack the capacity due to geopolitical constraints. Therefore, I don’t expect major progress in financing. The GGA will likely be approved, but implementing national adaptation plans will require USD 6–7 billion annually — and it’s unclear where that money will come from.”

Under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, carbon trading was adopted at the Baku COP, and discussions will continue in Belém to make it more effective.

In an interview with Energy & Power, Ziaur Rahman, Founder and CEO of Recycle Jar Ecosystem Ltd., said: “Bangladesh has significant potential to access large-scale funding for climate action through carbon trading. By 2030, the global voluntary carbon market is projected to reach between USD 800 billion and USD 1.0 trillion. If Bangladesh prepares properly, it could easily claim a 1% share of that market. However, to achieve this, Bangladesh must establish a national carbon exchange, following the example of other countries. We are currently working toward that goal.”

Bangladesh’s NDC also includes provisions for mobilizing climate finance through carbon trading. However, Dr. Manjurul Hannan Khan pointed out that: “While the project approval authority has been finalized, Bangladesh is still far behind in developing the necessary human resources — project developers and validators — needed to access carbon finance. The country must strengthen its institutional capacity to fully benefit from carbon trading.”

To limit global temperature rise to 1.5°C, the world has no alternative but to take ambitious emission reduction actions. Although the deadline for submitting NDCs has passed, only 67 countries, including Bangladesh, have submitted theirs.

According to the NDC Synthesis Report, the countries responsible for 70% of global emissions have yet to submit updated NDCs. Even if all existing commitments are fully implemented, global emissions would fall by only 17% by 2035, whereas achieving the 1.5°C goal requires a 60% reduction during that period.

The report estimates that implementing 64 submitted NDCs will require USD 1.97 trillion, of which USD 1.07 trillion is expected to come from international assistance, while domestic investments will cover only USD 225 billion.

Bangladesh’s NDC follows a similar pattern — it estimates that achieving a reduction of 85 million tonnes of carbon emissions by 2035 will require USD 116 billion in investment, of which USD 90 billion is expected from global sources.

There is no doubt that discussions in Belém will be lively and intense over carbon emission reduction and Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). What makes this even more pressing is that even the European Union — which has traditionally led on emission reduction — has not yet submitted its updated NDC.

According to Ziaul Haque, the Belém COP could create an opportunity to encourage remaining countries to submit their NDCs. Although following the International Court of Justice’s (ICJ) advisory opinion on climate impacts, it was expected that countries would present ambitious and effective emission reduction plans, that has not happened in practice.

At the Dubai COP, the Loss and Damage Fund was finalized. So far, only USD 779 million has been pledged to the fund, and since Dubai, there has been no additional commitment. The fund’s management board has decided to allocate USD 250 million to vulnerable and affected countries under specific projects. The fund will become operational from the Belém COP, starting with a call for project proposals.

However, the Leaders’ Summit, scheduled for November 6–7 in Belém, is unlikely to bring new pledges to the fund, leaving the Global South pessimistic about fresh financial commitments.

To achieve the global goal of reducing carbon emissions and stabilizing temperatures, countries must gradually phase out fossil fuel use. At the Dubai COP, countries agreed — without specifying a timeline or method — to transition away from fossil fuels. Yet, no progress was made on this at Baku, and there are no visible signs that it will advance in Belém either.

However, the world is working to finalize a Global Just Transition Roadmap. Global civil society expects that Belém will see the conclusion of a “Belém Action Mechanism for Global Just Transition,” which will enable collaboration among Parties and stakeholders. The plan is to continue this work until COP32, by which time a final roadmap for implementation could be adopted.

Alongside the decision to phase out fossil fuels, the Dubai COP also saw a global agreement that by 2030, every country will triple its renewable energy capacity and double its energy efficiency.

So far, 44 submitted NDCs have reiterated commitments to triple renewable energy capacity. Countries such as China, India, and those in the European Union are already working toward this goal. However, experts note that to triple renewable capacity by 2030, an annual growth rate of 4% is needed — whereas current growth remains at 2% or less. The world is also lagging in achieving its target to double energy efficiency.

The hopeful sign is that Bangladesh — which currently lags in renewable energy deployment — is expected to significantly increase its capacity by 2030, meeting its target. Moreover, Bangladesh’s annual growth rate in energy efficiency is 1.5%, indicating that the country is on track to meet its goal.

In an interview with Energy & Power, Dr. Shahi Md. Tanvir Alam, a Bangladeshi researcher working with the Czech Republic’s Just Transition Project, said: “The European Union has set a target to achieve 43.5% renewable energy capacity by 2030, but in reality, it aims for 45%. In 2023, EU countries invested a total of USD 1.18 billion in expanding renewable energy, while at the same time providing USD 204 billion in subsidies for fossil fuels. At this investment rate, the renewable energy target will not be achieved. Moreover, to double energy efficiency, an annual growth rate of at least 4% is required, but currently, it is only 2–3%.”

Although there has been little visible progress globally in reducing fossil fuel consumption, massive investments are being made in carbon reduction technologies — such as carbon capture and storage (CCS). Countries like China are investing heavily in renewable energy, but they continue to maintain substantial investments in fossil fuels as well.

Meanwhile, the world has embraced nuclear power as a form of non-carbon electricity. Apart from a few European countries, many nations are now planning large-scale investments in nuclear energy.

It is being observed that both developed and emerging economies are increasing their investments in domestic energy sectors — particularly in military and security spending — thereby reducing their capacity to contribute to climate finance.

However, M. Zakir Hossain Khan, Co-founder and Managing Director of Change Initiative, disagrees with this justification. He stated: “Last year, the world invested more than USD 4.0 trillion in the military sector and provided USD 1.3 trillion in fossil fuel subsidies. Investing in the military for self-defense will not protect them from future environmental risks. Therefore, the Global South must become more active in pressing these countries to invest in climate action.”

Climate negotiations are, in essence, driven by two forces — science and politics. Within the framework of the UNFCCC, decisions are not taken through democratic voting but through consensus. As a result, global climate negotiations are controlled by politics rather than science, causing repeated failures in both strategy and implementation in addressing climate impacts.

Still, hope remains. The Belém summit presents an opportunity to revive global commitment and rebuild trust. Brazil’s leadership, rooted in both moral authority and environmental symbolism, could help steer negotiations toward meaningful outcomes. For that to happen, delegates must move beyond empty pledges and focus on actionable commitments: transparent carbon reporting, accelerated renewable energy transitions, and equitable climate financing mechanisms that empower the most vulnerable.

If COP30 can restore the spirit of shared responsibility that once defined global climate action, it may yet keep the 1.5°C goal alive. The world cannot afford another round of promises without progress. The time for hesitation has passed – what Belém needs to deliver now is conviction, cooperation, and a clear roadmap for survival.

Download Cover As PDF/userfiles/EP_23_10_Cover.pdf