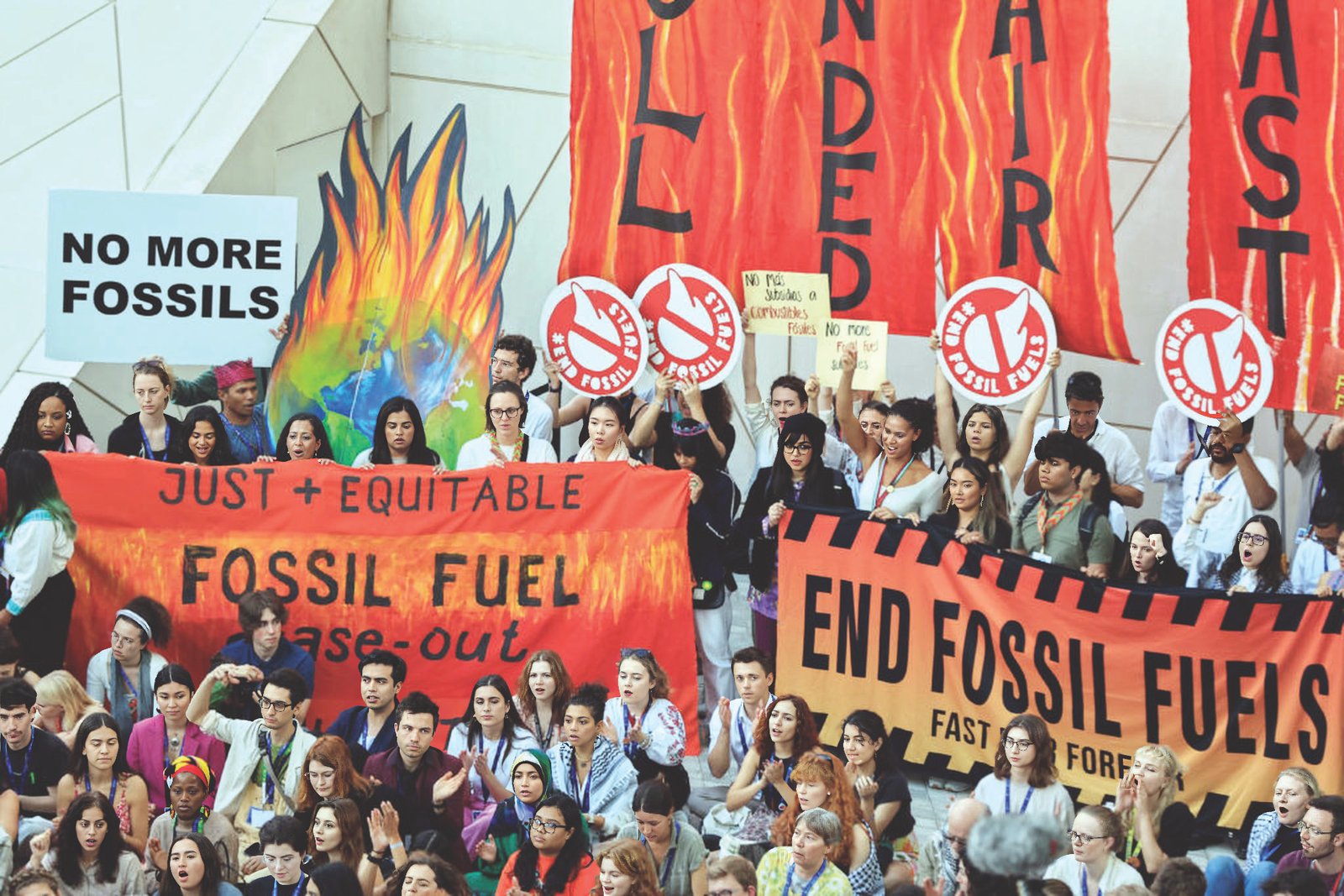

When world leaders gather in Belém, Brazil, for COP 30 in November 2025, the stakes will be unusually high. After nearly three decades of climate conferences, the world is not short of declarations, roadmaps, and carefully crafted communiqués. What it lacks is credibility. Emissions continue to rise, fossil fuel production plans remain incompatible with net-zero pledges, and finance commitments made more than a decade ago are still unmet. Against this backdrop, COP 30 will be judged not on the poetry of new promises, but on the prose of concrete delivery.

The contradictions in global climate governance are by now painfully familiar. Governments pledge climate neutrality by 2050 or 2060, yet continue to approve new coal mines and oil fields. They speak of just transitions, but fail to provide communities with viable alternatives when carbon-intensive industries decline. They invest in renewable capacity, while still allocating hundreds of billions of dollars to subsidize fossil fuel consumption. These are not marginal inconsistencies; they are systemic patterns that erode the credibility of the entire system.

The credibility gap is not just a diplomatic problem—it is also a political one. Citizens and businesses who hear lofty rhetoric but experience contradictory policies grow cynical about the seriousness of climate leadership. Investors hesitate when they see governments subsidizing fossil energy at the same time as they claim to be phasing it out. The perception of incoherence weakens confidence and slows down the mobilization of private capital, which is essential for the transition. In short, when ambition is not matched with consistency, the result is paralysis.

This is why COP 30 is already being framed as a “credibility summit.” Its host, Brazil, sits at the heart of the global climate story: a country rich in renewable resources, a leader in biofuels and hydropower, but also custodian of the Amazon rainforest, one of the world’s greatest carbon sinks and ecosystems. The symbolism is powerful. Belém is not just another conference venue—it is a city at the edge of the Amazon, where the gap between words and deeds will be tested. For Brazil, and for the world, the question is whether COP 30 will mark a turning point in restoring trust in climate governance!!!!

The European Union is often portrayed as the global frontrunner in climate leadership. It was the first major bloc to implement a large-scale carbon market, the Emissions Trading System (ETS), and it has enshrined climate neutrality into law as part of the European Green Deal. Over the past two decades, the EU has shown that policies once dismissed as politically or economically unrealistic can, with persistence, become the cornerstone of mainstream governance. Carbon prices, once languishing at token levels, have risen significantly since 2018 reforms strengthened the system. This created clearer signals for investors and helped to accelerate the deployment of renewables.

Yet the EU’s leadership story is also one of contradiction. Fossil fuel subsidies have continued across the bloc, often justified as emergency measures during times of crisis. When energy prices soared in 2021–2022, many governments spent billions to shield households and industries, but in practice, these measures blunted the price signals intended to accelerate the transition away from fossil fuels. Such interventions are politically understandable—no government wants to preside over widespread fuel poverty—but they weaken the credibility of long-term commitments.

Public investment has also followed an uneven pattern. At times, the EU has mobilized major resources to support clean technologies and infrastructure, such as through the NextGenerationEU recovery plan. At other moments, investment has stagnated or been reoriented toward short-term concerns. This inconsistency creates uncertainty for private investors, who often need long-term clarity before committing capital to projects with horizons measured in decades. For companies weighing whether to expand clean energy capacity, this policy volatility undermines confidence.

The lesson from the EU is not that ambition is futile, but that ambition without coherence falls short. A strong carbon price loses credibility if subsidies dilute its effect. Investment programs inspire less confidence if they appear cyclical rather than sustained. For the international community, the EU example is a reminder that even in advanced democracies with sophisticated institutions, short-term politics can derail long-term strategy. If Europe, with its resources and capacity, struggles to eliminate contradictions, the challenge for others is even greater.

If Europe’s contradictions illustrate the difficulty of aligning ambition with action, the global picture is even more sobering. Fossil fuel subsidies remain deeply entrenched in nearly every region of the world. According to the International Energy Agency, direct subsidies for fossil fuel consumption exceeded $1 trillion in 2022, largely as governments sought to protect households and industries from soaring energy prices. While many of these measures were presented as temporary crisis responses, their long-term effect is to entrench fossil dependence and consume resources that could accelerate clean energy investment.

The persistence of subsidies is rooted in politics as much as economics. Energy is not simply a commodity; it is a basic necessity and a potent political symbol. In many countries, subsidies are defended as vital to social protection, ensuring that the poorest households can afford fuel and electricity. Yet in practice, the bulk of benefits often flow to wealthier households, who consume far more energy. This makes subsidies regressive, costly, and socially inefficient. Still, they are politically sticky.

Examples abound. In Nigeria, repeated efforts to cut fuel subsidies have sparked protests and political crises, forcing governments to backtrack. In India, fuel pricing reforms have advanced in fits and starts, constrained by electoral pressures. In the Middle East and North Africa, subsidies are woven into the social contract, making reform politically explosive. Even in advanced economies, subsidies persist through less visible mechanisms such as tax breaks, royalty relief, or emergency bailouts during price spikes. The pattern is consistent: when faced with political risk, governments fall back on fossil support.

The implications for global climate credibility are serious. While governments continue to subsidize fossil consumption, carbon pricing schemes remain fragmented and underpowered. Fewer than 5 percent of global emissions are priced at levels consistent with Paris Agreement pathways. The paradox is glaring: the world spends vastly more to support fossil fuels than to penalize them. For investors, businesses, and citizens, this raises an obvious question: how serious are governments about the energy transition if they continue to prop up the very fuels they claim to phase out?

For COP 30, this paradox cannot be ignored. A summit focused on credibility must directly address fossil subsidies. While reforms are politically difficult, credible pathways exist. Governments can pair subsidy reductions with targeted cash transfers or investments in public services to protect vulnerable groups. They can design gradual phase-outs with clear milestones, reducing the risk of backlash. Above all, they can acknowledge that subsidizing the fuels of the past while claiming to build a future of clean energy is a contradiction that undermines trust.

While subsidies reveal the inertia of the old energy system, technology illustrates the dynamism of the new. Over the past two decades, the cost of clean energy technologies has fallen dramatically. Solar photovoltaics, once considered prohibitively expensive, are now the cheapest source of new electricity generation in many parts of the world. Onshore wind has followed a similar path, and offshore wind, though more capital-intensive, is rapidly scaling. Battery costs have declined by more than 80 percent since 2010, making large-scale storage increasingly viable.

Yet falling costs alone do not guarantee deployment. Policy frameworks, public investment, and industrial strategies remain decisive in shaping outcomes. Where governments provide predictable support—through tax incentives, long-term auctions, or stable regulatory frameworks—renewables flourish. Where support is inconsistent, progress stalls. The United States offers a clear example: the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 created strong and durable incentives for clean energy deployment, triggering a wave of private investment. China has pursued a different path, combining state-led industrial policy with scale advantages to dominate solar, batteries, and electric vehicles.

Industrial policy is now at the heart of global climate geopolitics. The EU’s Green Deal Industrial Plan, the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act, and China’s state-led expansion all reflect recognition that clean technologies are not just tools for decarbonization but drivers of competitiveness and national security. This competition carries risks of fragmentation, such as trade disputes and unequal access to technologies. But it also demonstrates that climate policy is no longer a peripheral issue; it has moved to the core of economic strategy.

For the Global South, these developments present both challenges and opportunities. Without access to concessional finance, many countries risk being locked into fossil pathways while watching the major powers dominate clean energy industries. But with the right support, they could leverage the transition to foster industrialization, create jobs, and diversify exports. The clean energy race need not be a zero-sum game; it could become a driver of inclusive development if finance and technology transfer are made central to global strategy.

The broader lesson is clear: technology creates the conditions for change, but politics determines whether those conditions are used. Falling costs can unlock opportunity, but public investment, industrial policy, and subsidy reform decide whether opportunities are seized. COP 30 will need to grapple with this dual reality: the tools for transition exist, but without coherent strategies and equitable access, they will not deliver the scale or speed required.

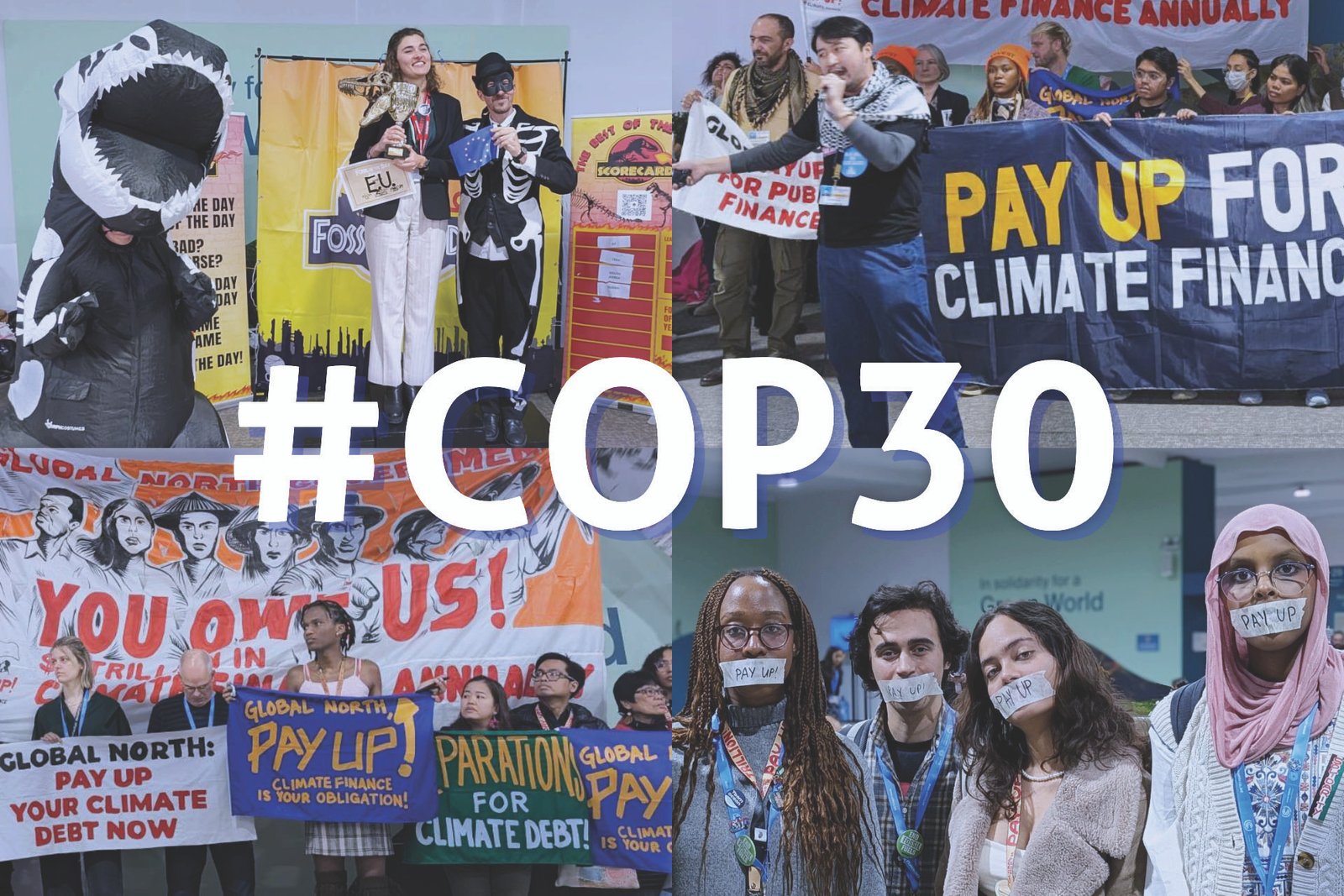

Finance has always been the weakest pillar of global climate governance, and it will be the make-or-break issue at COP 30. The $100 billion per year pledge made by developed countries in 2009 was meant to symbolize solidarity and trust. More than a decade later, it has still not been fully met. Accounting disputes aside, the perception in the Global South is clear: promises have not translated into delivery. For many governments, this failure is not just about money; it is about credibility. If the words of leaders cannot be trusted, what basis is there for future cooperation?

The scale of finance required dwarfs the original pledge. Trillions of dollars are needed annually to fund mitigation, adaptation, and resilience in developing countries. Yet many of these countries face borrowing costs two or three times higher than those of advanced economies, even for projects that are technically and economically sound. This structural inequality traps them in a vicious cycle: unable to access affordable capital, they cannot scale clean energy, and without scaling clean energy, they cannot reduce risks that keep borrowing costs high.

Brazil’s leadership as host gives COP 30 a unique character, I think. As custodian of the Amazon, Brazil embodies the intersection of climate, development, and ecosystems. Protecting the rainforest is not just a national concern; it is a global imperative. At the same time, Brazil is an emerging clean energy power, with vast potential in wind, solar, and biofuels. Hosting COP 30 allows Brazil to highlight these intersections and to amplify the demands of the Global South for a more equitable climate regime. Its leadership can shape the narrative around justice, finance, and ecological stewardship.

The Global South agenda is clear: finance must be predictable, transparent, and accessible. This means moving beyond ad hoc pledges to institutionalized mechanisms. It means scaling concessional finance, reforming multilateral development banks, and exploring innovative instruments like debt-for-climate swaps. It also means recognizing that climate finance cannot be separated from development finance. For countries facing poverty reduction, infrastructure gaps, and climate risks simultaneously, integrated strategies are essential.

COP 30 in Belém offers a chance to reframe climate finance not as charity but as investment in a stable, resilient global future. Without such a shift, the credibility gap will widen, and trust in multilateralism will erode further. With it, however, the world could turn a corner—building the financial foundation for a transition that is both ambitious and just.

The lessons from Europe, from global subsidy patterns, from technology shifts, and from finance debates converge on a single point: credibility depends on coherence. At COP 30, leaders cannot rely on new slogans or distant targets. They must show that the policies they enact today align with the futures they promise tomorrow. For this, a practical policy roadmap is essential—one that bridges ambition with delivery, and rhetoric with reality.

The first priority is fossil subsidy reform. No climate strategy can carry weight while governments continue to spend hundreds of billions each year making fossil fuels artificially cheap. Reform does not mean sudden removal; it means transparent timetables, gradual phase-outs, and well-designed social protections. Targeted cash transfers, investments in efficiency, or expansion of public services can shield vulnerable households far more effectively than blanket subsidies. This is not only fiscally prudent but socially fair.

The second priority is robust carbon pricing. Today, fewer than 5 percent of global emissions are priced at levels consistent with Paris Agreement pathways. To change this, governments must commit to progressively higher carbon prices and explore linking regional systems for stability. Yet pricing alone is insufficient. As the European example shows, carbon prices must be supported by complementary measures. Without subsidy reform and consistent investment, carbon markets risk becoming expensive exercises in symbolism rather than engines of transformation.

The third priority is stable and targeted public investment. Governments should focus on enabling infrastructure—grids, storage, interconnections—that make large-scale deployment possible. They must also direct resources toward innovation in harder-to-abate sectors such as steel, cement, and aviation. In developing countries, concessional finance should reduce risk and crowd in private capital. Public money should not substitute for private investment but leverage it, unlocking scale.

The fourth priority is financial credibility. Delivering on the $100 billion pledge is the bare minimum; designing predictable, transparent, and equitable flows is the real challenge. This requires reforming multilateral development banks, scaling climate funds, and integrating climate finance into broader development strategies. Trust cannot be rebuilt with vague promises—it requires delivery mechanisms that citizens and investors alike can observe.

Finally, leaders must recognize that policy coherence is not a technical exercise but a political choice. Fossil subsidy reform, carbon pricing, investment, and finance are not separate boxes to tick; they are interdependent levers that succeed or fail together. Align them, and the transition accelerates. Fragment them, and credibility collapses.

COP 30 in Belém is therefore more than a negotiation—it is a test of political courage. The Amazon, the finance gap, the rising demand for justice from the Global South—all will converge on a single question: can governments finally align their words with their deeds? If they can, COP 30 may be remembered as the moment when the credibility of climate governance was restored. If they cannot, the erosion of trust may become irreversible, with consequences for the planet and for global stability alike.

Download this Article As PDF/userfiles/EP_23_10+COPS_Tanvir.pdf

Dr. Shahi Md. Tanvir Alam, Visiting Researcher, RIS MSR 2021+ Project, School of Business Administration in Karviná, Silesian University in Opava, Czechia, Email: tanvir@opf.slu.cz /shahi.tanvir@gmail.com